Come to think of it, there are many genres of manga. From battles, sports, cooking, science fiction, to romance…. There have been many different kinds of manga born in the past, in the past, present, and future, and read by countless people. As an unparalleled manga lover, I too have loved works of all genres and have introduced many manga artists on this blog. I have introduced a number of manga artists on this blog, and a question occurred to me.

What is the oldest genre of manga?

There are many theories, but it seems that to know the answer to this question, we need to go back to the origins of the expression “manga” itself.

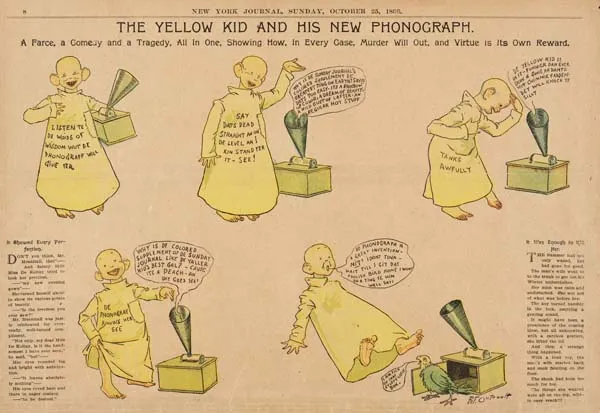

Cartoons are a form of entertainment in which characters are drawn on paper and made to talk to each other by adding speech balloons. This method of expression may seem commonplace to us today, but in fact it was not only commonplace, it was unimaginable until the late 19th century. This is because there was no concept or experience of “hearing speech without the speaker himself” (although there were of course musical scores and discourse records, these did not reproduce the generated sound itself). In the 1890s, however, the number of American households with access to phonographs increased dramatically. Then, in a certain newspaper magazine, a work was born that overturned the conventional techniques of expression.

This is a cartoon by R. F. Outcault titled “The Yellow Kid and the New Phonograph,” which appeared in the New York Journal on October 25, 1896. It is a comedy in which a boy introduces a phonograph and plays a sound, only to find that the owner of the voice is actually a parrot. This type of comedy was born out of a time when the experience of “hearing words without a speaker” was a novelty, and the “speech balloon” form of expression was adopted as a result of a trial-and-error process to incorporate this experience.

Now, have you figured it out by now? Yes, of all the genres of manga in this world, the oldest is the gag manga, whose origins can be traced back to the very method of expression itself.

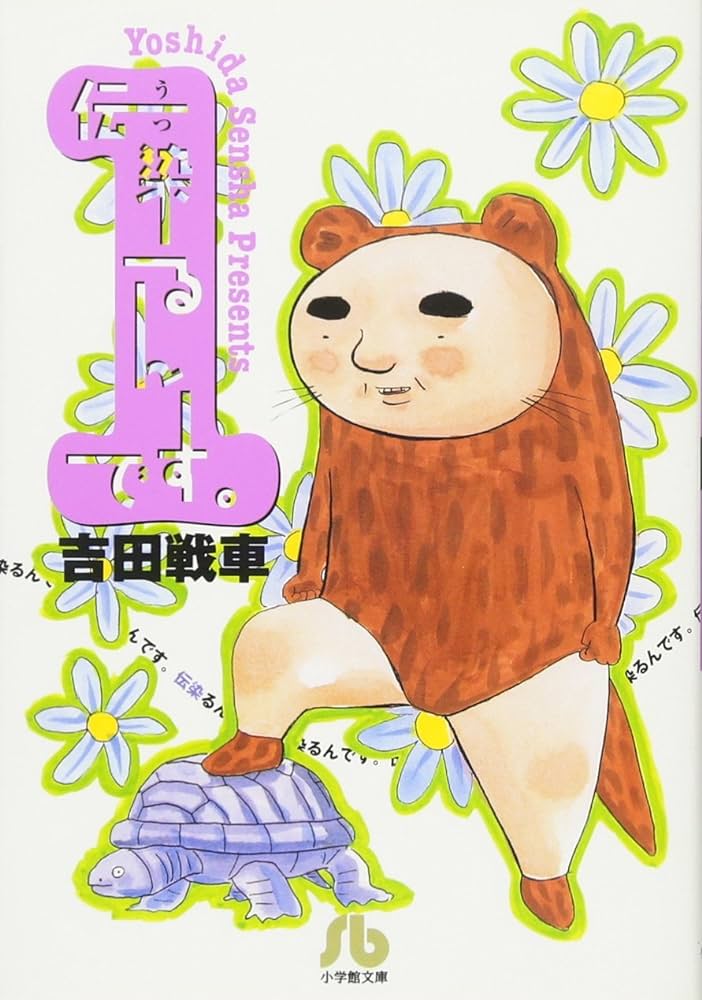

In this article, I would like to introduce one of the most famous gag cartoonists, Yoshida Sensha. (The above lengthy explanation is, of course, for the sake of introducing him.)

A Brief Introduction to Yoshida Sensha

Yoshida Sensha (August 11, 1963) is a Japanese manga artist. Born in Mizusawa City (now Oshu City), Iwate Prefecture, he made his debut in 1985 with “Pop Up” (VIC Publishing).

In 1989, he began serializing “Utsurundesu” in “Big Comic Spirits” (Shogakukan).

He has worked on manga, essays, illustrations, and corporate character design for magazines, newspapers, websites, and other media. At one time, he was regarded as a representative of absurd gag manga, but his main interest lies in the world of fairy tales and nonsense, where non-human animals, plants, space creatures, and even non-living things have wills and words.

His best-known work, “Utsurundesu”

It is regarded as a monumental work, a pioneer in the establishment of the absurd gag manga genre, overturning the conventional wisdom of four-frame manga, in which the beginning, middle, and end of a story were absolute requirements. After its serialization, it spawned many subgenres and spread similar tastes not only in the manga world but also in the comedy, entertainment, and commercial industries. This is considered a paradigm shift for “gags”.

”Utsurundesu” challenges the limits of nonsense

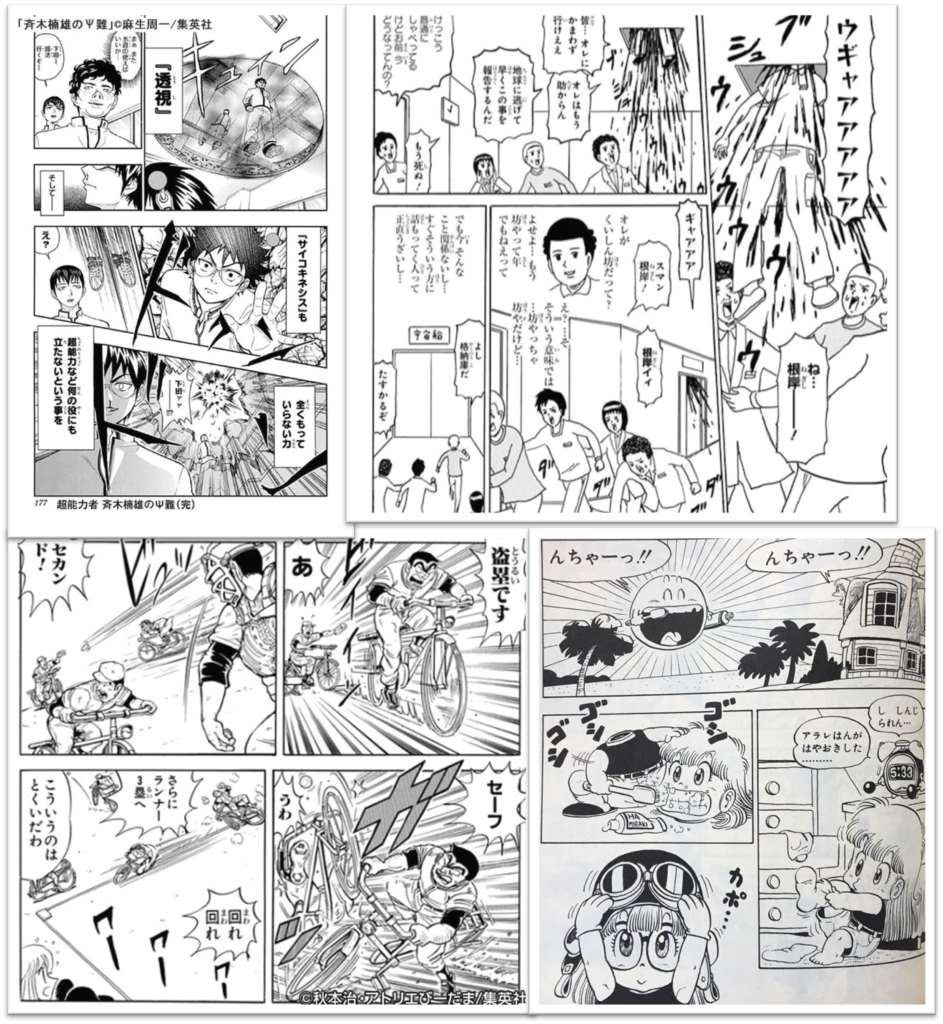

In contemporary Japanese “gag manga,” many of the characters are depicted as outlandish or abnormal in their behavior.

This style tends to be favored, especially by children, because it is more pictorial and more easily conveyed to the reader.

Yoshida’s works, however, are different. He does not use flashy “actions” of characters, but rather “language” or “concepts” to evoke laughter. He uses words that we use casually in our daily lives to make us laugh. In addition to being funny, Yoshida’s cartoons also make us look at language from unexpected angles, exposing how strongly we are bound by language. I believe this is Yoshida’s one and only originality.

But I can’t begin to describe his originality, no matter how much I say. Let’s quickly pick up a few gems from his masterpiece “Utsurundesu,” a four-frame manga.

・”be careless ” and ” doing something irreversible”

First of all, please take a look at this work.

Originally, “be careless” was supposed to be a state of mind that occurs unconsciously. However, the main character intentionally tries to do this, and as a result, his wife is cuckolded. I would like to appeal the excellence of this work right now, but before I do so, I would like you to watch this other work first.

This work depicts the nonsense of voluntarily putting natto (a very sticky, traditional Japanese food) into a machine. This work, like “be careless,” uses a certain word in a different way than usual, and the nonsense that results is expressed in an amusing way. Both works are excellent in that they take a look at words that abound in our daily lives from novel angles and make us think, “I see what you are getting at. However, if I were to rank the two works in a pecking order, I would put the “be careless” work above them.

If nonsense is one of the dividing lines in whether or not a work can evoke laughter, then this “be careless” is more nonsensical than the other one. For example, “doing something irreversible” is, of course, an “action,” so if one wants to practice it, one can do so. On the other hand, “be careless” is, as mentioned above, a “mental state,” which cannot be achieved even if you intentionally try to do so. Rather, it is a word that is set to the point where, because it is a state of high unconsciousness, it “comes to an unwilling end,” such as when one’s wife is cuckolded by another person. This “be careless” is a masterpiece compared to ” doing something irreversible”. By comparing the two, I hope you can understand the prominence of the “be careless” work.

In this way, Yoshida’s greatest forte lies in the way he reverses the meaning of the word and subverts the concept of the word.

・From Nonsense to Possible Worlds

For example, I dream that I am back in my school days, and I wake up in the morning with a start. And then,

“Oh,I don’t have to go to school anymore.”

We have all had this experience.

In other words, this manga is based on the universal experience of the abundant repetition of “going to school,” even after graduation, which transcends time and evokes the illusion that “I don’t have to go to school anymore.

The interesting part is that a person just after graduation, or even an old woman, can fall into such an illusion just by being asked from behind by a mysterious life form (two sparrow-like creatures on a power line).

The fact that they don’t react to being asked suddenly, without any context, if they really don’t have to go to school is nonsense, and the fact that they just ponder, “Do I really have to go to school?” is nonsense, and the fact that good old adults are so upset about it is also funny.

But that is not the great thing about this work. If it were to stay with the above content, perhaps even an ordinary gag cartoonist could have arrived at this point. Instead, the most outstanding aspect of this work is that it features a baby.

Other than the baby, the other adults in the story have attended school before, so it is not impossible for them to fall into the illusion described above, or at least, it is a hundred steps away. However, it is absolutely impossible for this baby. In other words, this work, too, succeeds in maximizing the aforementioned “impossibility” by introducing a baby, and in demonstrating its nonsense to the fullest extent.

Further still, here I would like to take one more step and dig deeper into this work.

There is a term in this world called “possible worlds.

This is a philosophical and logical term, originally a concept used by Leibniz to explain his best world view.

A possible worlds is a world that is different in some respects from the world we actually live in, but logically enough, we can think of it as another world. It is often used as a setting for stories, and everyone at one time or another has dreamed of an alternate worldline that is different from the current world. And if we are forced to apply this concept to this work as well, their illusion of “having to go to school” could be a variant of the possible world, though perhaps in a slightly different direction. In this work, the old woman and two other middle-aged men are probably living on pensions or working in companies, and are busy with their daily lives. In such a situation, one world line, “going to school,” suddenly emerges with a single voice of a sparrow. This is because, as I have mentioned many times before, they had attended school in the past. In other words, what this possible world relies on is the past, or memory.

If you think about it, this possible world may be very dangerous. Memory is a very ambiguous thing. It is a world of possibilities that is transformed by misunderstandings, confusions, overwrites, and other malfunctions that occur frequently to all of us, and that sometimes take on a completely different form. This is where the baby comes in.

One would laugh at the baby’s relieved expression in the last panel. This is because they think that it is wrong for a baby to be relieved that it did not have to go to school, even though it is not supposed to have any memories of “going to school”. But perhaps that is wrong. As mentioned earlier, it is a laughable act to put faith in “the past is a fact” by relying on memories. How can we say that their possible world is more certain than that of a baby?

I think that this work expresses Yoshida’s view of memory. People who have absolute faith in memory laugh at the illusion of babies. But sometimes, readers like me, who have a unique perspective, ask ourselves

“Is the baby really more nonsense?”

If Yoshida even envisioned the existence of such a possible world, it would be amazing.

Conclusion

Yoshida brought laughter to people by depicting the “impossibility” of language to the maximum extent possible and by fusing pictures and language. It has been exactly 30 years since “Utsurundesu. The trademark “Kawaso-kun” may have become an unfamiliar character to the younger generation.

Perhaps in keeping with the changing times, the world of manga is also undergoing a major transformation. Especially on social networking services, manga works that focus on eroticism and grotesqueness, with the aim of gaining more impressions, have been dominating the market. In this age, the only thing that is required is the intensity of the pictures, which can be recognized at a glance. In such an age, a manga that “combines pictures and language,” such as Yoshida’s, is naturally a poor match.

What would the creator of the “speech balloon” think if he were to see this situation? I can almost hear him saying, “Please don’t disrespect my invention.”

But please do not worry. There are people in Japan today, including Yoshida, who are fighting in the manga world in the name of “fusion of drawing and language. That is why I, too, must make efforts to spread the word about these artists, without being “careless”.

★Writer of this blog: Ricky★

Leave it to us for all your cultural needs! Ricky, our Japanese culture evangelist, will turn you into a Japan geek!

authority

・M studies [Discussion] The Hundred-Year-Old Origins of Contemporary Japanese MangaFrom imports and translations to domestic production (Ike Exner)

・Yoshida Sensha, Wikipedia