I have introduced Osamu Tezuka and Yoshiharu Tsuge as two of my “favorite manga artists” in my blog, and I would like to introduce Iwo Kuroda, a manga artist who is no less than both of them. Although he is a rather maniacal artist, a look at his career reveals that one of his works was highly praised by Hayao Miyazaki, and has been adapted into an anime by Ghibli and a TV drama by Nichi-Tele. However, even so, Kuroda Iwo’s current reputation as a “manga artist known only to those in the know and accepted by experts” is probably about as high as it can go. I was not happy about that, so I thought about how I could convey the appeal of Kuroda Ioichi through this blog. What I came to realize is that Iwo Kuroda is a cartoonist who is a master of rare cartooning techniques.

In this article, I would like to introduce his career and representative works, with a particular focus on his taste, precision, and novelty in his manga techniques, and explore them in depth.

Brief Introduction to Kuroda Iwo

His date of birth was January 5, 1971. Born as male and female twins. Born in Eastern Japan. He graduated from Hitotsubashi University, Faculty of Law and Faculty of Sociology, and made his debut in “Gekkan Afternoon” in 1993. In 2002, “Sexy Voice and Robo” won the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Award in the Manga Division of the 6th Japan Media Arts Festival.Incidentally, Hitotsubashi University, from which he graduated, is one of the top national universities in Japan. It is true that the conversational drama woven by the characters in his works is stylish and retorical, and the high linguistic level of the artist is evident. However, he is also a prolific writer, with only 13 serialized works and 4 short stories to his credit.

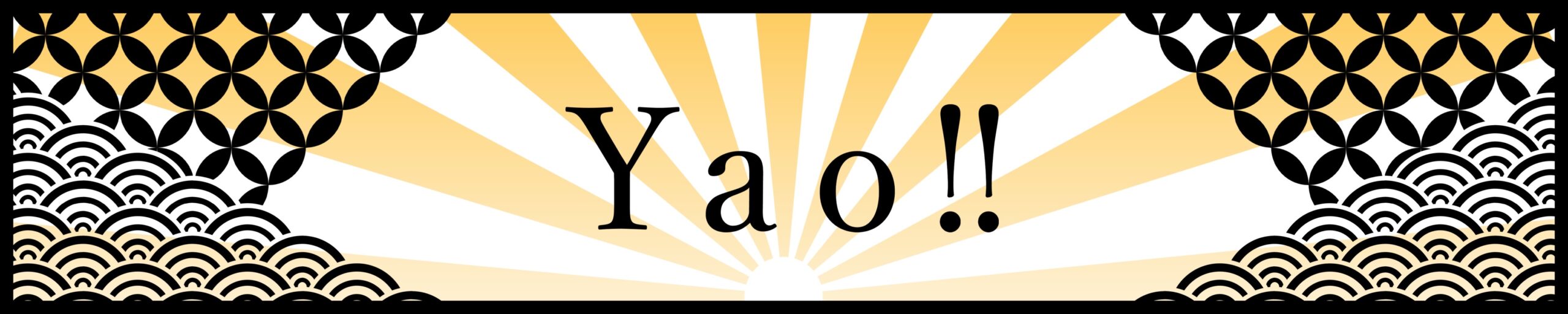

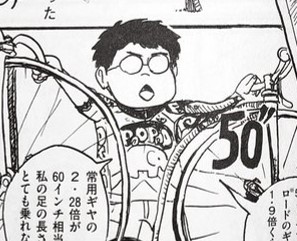

Masterpiece “Eggplant”/”Summer in Andalusia”

Kuroda Iwo’s most famous work is “Eggplant”

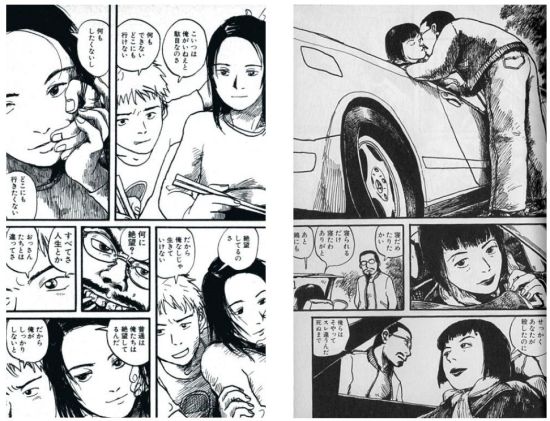

As the title suggests, this is a collection of short stories in which eggplants appear in each story. The title “Eggplant” is quite unusual. It is typical of Sulfur Kuroda to dare to use such an ingredient, which is not so conspicuous among vegetables, is not liked by many people, and does not have much nutrients. Eggplants appear in each story, but they are neither liked by the characters nor are they the main topic of the story. It appears at an ordinary time and ends without much activity. But that is surprisingly pleasant. The characters in the film are quite ordinary, and like eggplants, they are unremarkable people of the city.

However, because he focuses on such people, Kuroda Sulfur succeeds in revealing their realistic psychological portrayal and detailed daily lives. The composition of “Eggplant” as “us in our daily lives” is suggested without being preachy. The most famous of the “Eggplant” short stories is “Summer in Andalusia”.

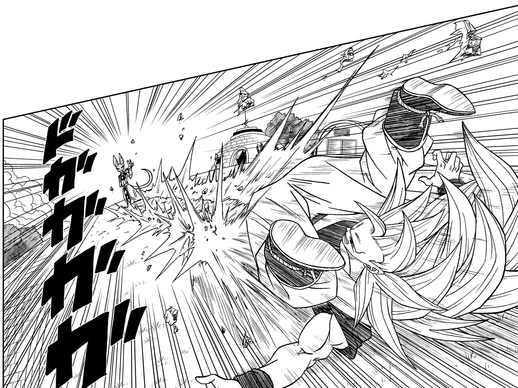

Set in the Vuelta a España, a Spanish cycling road race, the story follows the protagonist as he goes about his “work” as a professional road racer, despite the threat of being fired and the complexities of his former lover’s marriage to his brother. Although it is only a 20-odd page manga, it is a masterpiece that is packed with the dynamism of the race, the boiling heat characteristic of Spain, and the stylish dialogue that could be called Kuroda’s “Kuroda-busi”. (Even Hayao Miyazaki sent a letter of recommendation, saying, “Anyone who understands the fun of this film is the real thing!)

Now, the introduction has gone on for a long time. Now it’s time to get down to the main topic of this article, the characteristics and techniques of Iwo Kuroda’s manga techniques.

Introduction to the characteristics and techniques of Kuroda Ioichi’s manga technique

・Elimination of symbols

A manga is a collection of expressive symbols. As shown in the red frame of the image, there are various symbols in manga that express emotions, and readers read them to determine whether the character is angry, impatient, or embarrassed (these symbols are said to have been created by Osamu Tezuka, but there are various theories). (It is said that this symbol was created by Osamu Tezuka, but there are many theories.) It is amazing that such simple lines can convey the psychology of a character so clearly. Manga from all ages, both East and West, have adopted this technique of expression, and readers have read and enjoyed them. However, Iwo Kuroda is a rare artist who has turned his back on this historical path. For example…

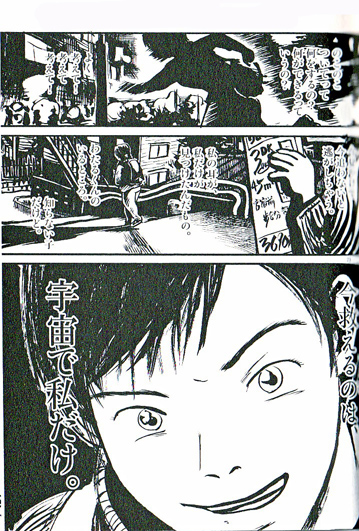

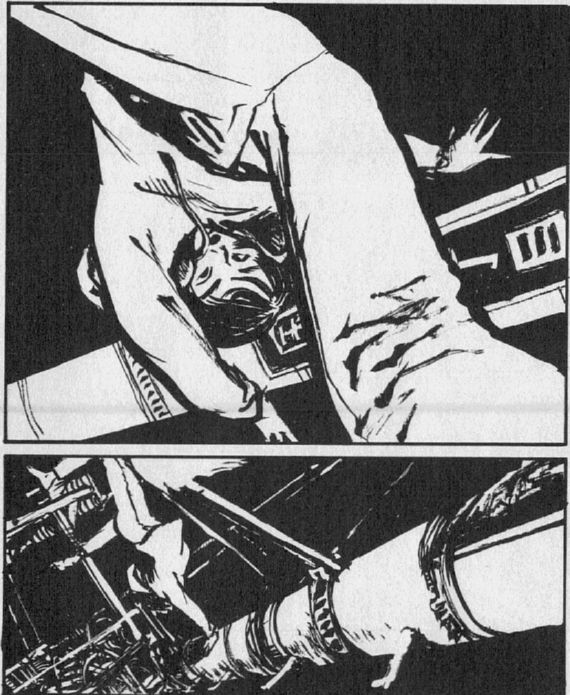

This is an excerpt from a scene in the film “Sexy Voice and Robot” in which the main character, Nico, goes to rescue a boy who has been kidnapped. It is a scene in which a junior high school girl is about to charge at the kidnapper, and she asks herself, “What can I do? and it is clear that she is also struggling with the situation. And yet, her face is devoid of the usual sweat symbols, as it should be there. An ordinary manga artist would have drawn the sweat symbols all over her face to give her an expression of tension. However, Kuroda does not use that method. And it is not just this scene. In all of his works, Kuroda thoroughly eliminates emotional symbols. In other words, Kuroda uses “situations” to convey the emotions of the characters to the readers.

I mentioned earlier the role of symbols, but in fact, symbols have an aspect that may be considered negative. That is, the presence of symbols makes it impossible to avoid a certain interpretation. In other words, once the symbols of sweat and anger are drawn on paper, the reader cannot read from these characters anything other than the emotions intended by the author. This is why Kuroda does not draw symbols.

But that, in a sense, requires literacy from the reader. In other words, for readers accustomed to symbols, when they see a character without symbols, such as in an image, they do not know what this person is thinking. That is why it is often said that “Kuroda Iwo’s manga is difficult to read” (hence, many manga artists use a lot of symbols to avoid this). However, Kuroda does not jump to this approach easily. He knows that not using these symbols rather gives the reader room for imagination. In creating a work of art, the character’s “emotion” should be treated with the utmost care.

What is this person thinking right now?

Is he/she angry or sad?

This kind of thinking about the character is the real thrill of appreciating a work of art. A thousand readers will give rise to a thousand different interpretations, and a work of art can be transformed into something completely different depending on the person who reads it.

・Disturbing Hiragana onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia in manga plays a role in explaining situations, creating atmosphere, and creating a sense of immersion. The presence of onomatopoeia can further heighten the excitement of a scene and create a three-dimensional effect that encompasses not only visual effects but also auditory effects, providing readers with a deep sense of immersion.

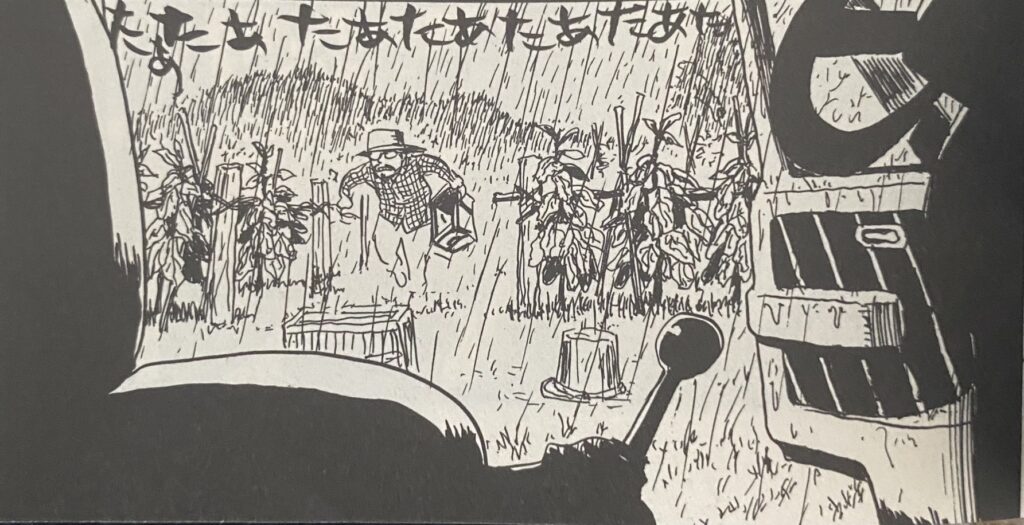

However, in Kuroda’s manga, onomatopoeia of a slightly different flavor appears. Typical of them are…

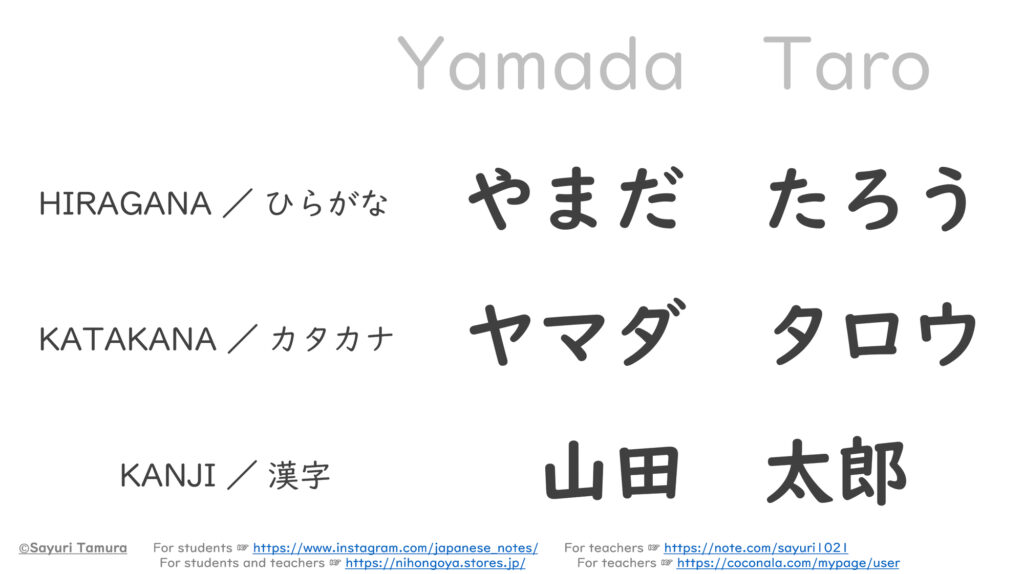

This “たあたあたあたあたあたあ” is the Hiragana character in Japanese (Japanese is composed of three characters: Kanji, Hiragana, and Katakana). The English translation of “たあたあたあたあたあたあ” is “taataataataataataa. It seems that there is no such sound as taataataataataa in this world, and it is inconceivable that such a sound could be emitted from rain. Furthermore, the onomatopoeia in Kuroda’s manga is placed so prominently in the pictures that the reader’s gaze is often diverted and his or her concentration is often distracted. However, Kuroda relentlessly uses such unusual onomatopoeia. In many cases, he uses Hiragana. Why in the world does Kuroda use such bizarre onomatopoeia with Hiragana so frequently? To analyze this question, it is necessary to understand how onomatopoeia was established in the Japanese language in the first place. While unraveling the history of onomatopoeia, let us look back at how the Japanese language was established.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

Historically, it is said that Kanji was first introduced from China, and that Hiragana and Katakana were born from Kanji (some say that there was an ancient script called Jindai-moji before the arrival of Kanji). (There is a theory that there were ancient characters called Jindaiji before the arrival of Kanji. For example, “山” means “mountain” and “木” means “tree. After Kanji characters were introduced to Japan, their meanings were compared with those of the Japanese language, and the Japanese language took root. This led to the creation of loanwords (Manyogana). Borrowed characters themselves had no meaning, but only represented sounds. However, the number of strokes in the loanword made it difficult to use, so it was gradually abbreviated as “a (Hiragana)” for “安 (loanword)” and “i (Katakana)” for “伊(loanword).” In this way, the loanword was used in the 8th and 9th centuries. In this way, Hiragana and Katakana are thought to have been established in the 8th to 9th centuries. Hiragana was systematized in the Heian period (794-1185), when it was used by women in particular, and in private letters and waka poems. Katakana is said to have originated among the priests of the Nara period (710-794), who wrote simplified versions of some of the loaned characters as kunjis (phonetic dots) for reading Chinese texts. From there, Hiragana spread as a women’s literature, while Katakana became necessary in practical use. After the Meiji Restoration, the introduction of foreign languages, and various other political and historical developments, the postwar national language policy officially established Hiragana as the norm for writing in the everyday language and Katakana as the national policy for writing foreign words and onomatopoeic words.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

The explanation is long, but in short, the Japanese language has historically consisted of three scripts: Kanji, Hiragana, and Katakana, each of which has a different role to play. Among them, Katakana is basically used for onomatopoeia in texts and cartoons. Of course, this culture has been followed from the moment manga was born and onomatopoeia began to be used, and even among contemporary Japanese manga artists, most of them use Katakana onomatopoeia. However, in spite of this historical background, Kuroda uses Hiragana onomatopoeia (do you understand the strangeness of this?). (You may have noticed this oddity.) In fact, he even writes onomatopoeic words that should not exist, such as “たあたあたあたあたあ” (taataataataa), in the panels without hesitation.

Onomatopoeia in manga generally appears within the panel in a form that is as unobtrusive as possible. As mentioned earlier, the role of onomatopoeia is to enhance the scene, to complement the picture, and to immerse the viewer. However, the onomatopoeia created by Kuroda is either nonexistent, out of place, or, dare I say it, “distracting. It is as if he is trying to prevent the reader from immersing himself in his world. Hiragana onomatopoeia creates a sense of de-immersion. Why does Kuroda take this approach? The answer will become clear in the next section.

・World deformation/de-immersion

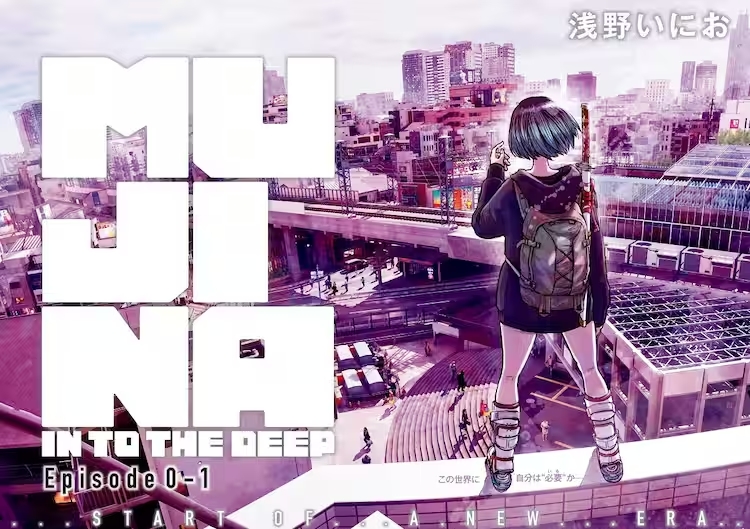

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Iwo Kuroda’s manga is its deformed worldview.

First, there are the paintings. His style, which favors the use of brush strokes, is often composed with a boldness that makes it look as if it were written in a single stroke. Some people may dismiss his drawings as “bad” or “hard to read,” but I feel that this is the true essence of Kuroda Iwo’s work.

Recently, I feel that the number of realistic manga has been increasing. The more realistic the manga is, the better it is, and the more immersive the drawings are, as if the world really exists. For example, “DRCL midnight children,” currently serialized in Grand Jump, is a typical example.

One of the factors driving this increase in the number of works is the development of technology. By tracing and digitizing photographs and using computer graphics to create realistic textures, landscapes that “look like the real thing” are being created.

On the other hand, however, there are creators who stubbornly defy this trend. They sometimes make readers and viewers feel uncomfortable with their rough lines, deformed characters, and absurd dialogues, as if they are trying to avoid immersion, and are sometimes criticized for this. If the goal of an artist who draws realistic pictures is to “make us forget that this is a manga,” the goal of an artist like Iwo Kuroda, who aims for deformation, is rather to “make us always aware that this is a manga. For example, this may be an animation story, but Isao Takahata of Ghibli is a typical example. In his posthumous work “The Tale of the Princess Kaguya,” there was a scene in which he instructed the animators to “make rough, pencil drafts at any rate.

The animators were perplexed as they worked, but the finished drawings looked as if they had been written in anger, as instructed, and Takahata was, of course, satisfied with the results.

(I will write more about Isao Takahata, the animation director, in another blog.

Why on earth would creators such as Kuroda and Takahata seek such deformed worldviews? I believe that they are asking us to “distance ourselves from the film” through their works.

Immersive entertainment these days is planning how to invite the reader/viewer/audience into the world of the work, how to make them assimilate with the main character. With the help of science and technology, backgrounds in comic books appear as if they are real, and in movies, seats move, people jump out of the screen, splashes of water spray, and so on, all in an attempt to make the viewer assimilate the main character. When the viewer finishes consuming the film, he or she feels as if it were his or her own experience. (After riding a Disney attraction, who would think, “What was the message in this?)

Takahata once said in an interview, “Fantasy is not image training for living in reality. He claimed that a story in which the protagonist fights valiantly in a world that is so realistically and perfectly created that the viewer cannot take away any message from it. In another interview, he said, “There are parts of the film that are not depicted, and there are parts that are not depicted.

I think that such works, with their undrawn parts and rough touches, evoke in the viewer the desire to search for memories and to imagine. I believe that the broken lines, thinning of the lines, and leftover paint in “The Tale of Princess Kaguyahime” may have served this purpose.

I think that Kuroda is probably trying to do the same thing. With the motto of “de-immersion,” Kuroda is testing the readers by drawing such rough lines.

Of course, we are not saying that it is just fine to be messy. They are all mobilizing their creative ambitions and exploring the maximum potential of their expressive techniques. They are always in thorough pursuit of unprecedented and novel methods. This leads us to the aforementioned onomatopoeia of Kuroda. Such use of onomatopoeia is unparalleled, and it has become synonymous with Kuroda among his fans. Or perhaps the fact that he does not use symbols (sweat and anger), a technique that has become a mere formality, may be due to the fact that Kuroda’s creative ambition and his motto of de-immersion are mixed in his mind.

Conclusion

Perhaps we, as discerning viewers, are finally motivated to read the message of a work when we are exposed to a novel technique. At the same time, it is only when we are able to finish viewing a work without becoming immersed in it that we are able to decipher the creator’s true intentions. I assert that no matter what the message of a creative work, no masterpiece will ever be created unless novelty and immersion coexist in the same way.

★Writer of this blog: Ricky★

Leave it to us for all your cultural needs! Ricky, our Japanese culture evangelist, will turn you into a Japan geek!

Sources

MAG2NEWS

Kuroda Iwo Wikipedia