In June 2024, the movie “Snake Path” was released. The film has attracted a lot of attention among movie fans, partly because it stars Kou Shibasaki, one of Japan’s leading actresses. However, the film is also known as a self-homage to the director, Kiyoshi Kurosawa. For those of us who love Kurosawa’s films, there is nothing more exciting than to see a parody of his immortal masterpiece made by someone other than himself.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa, by the way, is a filmmaker fascinated by jibaku-rei.

Various types of Jibaku-rei appear in his films. Some Jibaku-rei become black stains and stick to the walls, while others wander around a house where they have committed suicide. As will be discussed later, Jibaku-rei’s superb direction may have played a part in making him famous as a master of horror films. Kurosawa has produced a wide variety of films, including yakuza, coming-of-age, science fiction, and spy films, but I believe that the reason he continues to be in the limelight as the standard-bearer of so-called Japanese horror films is due to the novelty of his ghost direction, especially the way in which he depicts the Jibaku-rei.

In fact, in the past, such Kurosawa-style jibaku-rei has been successfully “staged” without even “appearing” in the film. That film is the original version of “Snake Path” mentioned above. I remember that when I first saw this film, my heart was reeling from beginning to end with an eeriness that I could not verbalize. If you only follow the storyline, it could be mistaken for a simple violent film, but it nevertheless evoked in me negative feelings of anxiety, discomfort, and fear. But, when I rewatched the film again with the release of the self-homage film, I came to realize that it was Jibaku-rei’s film.

What does it mean that Jibaku-rei “directed” the film without “appearing” in it?

And why is he so obsessed with the existence of Jibaku-rei?

What is his message that he pours into the concept of Jibaku-rei?

In this blog, I would like to clarify these questions.

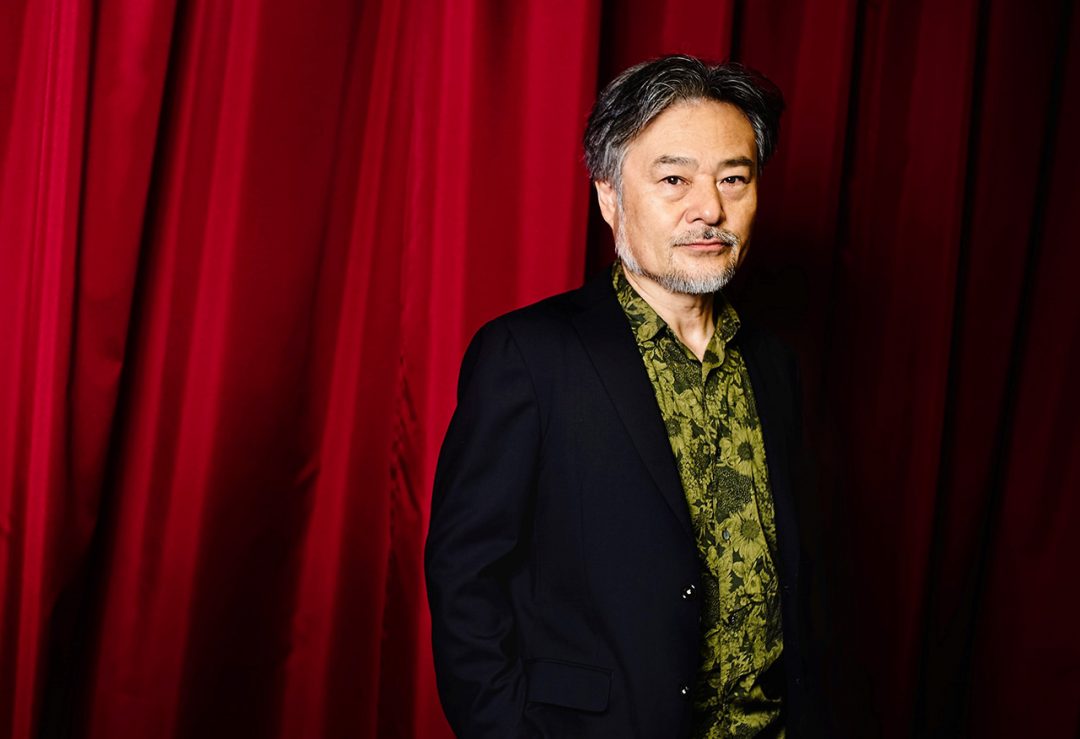

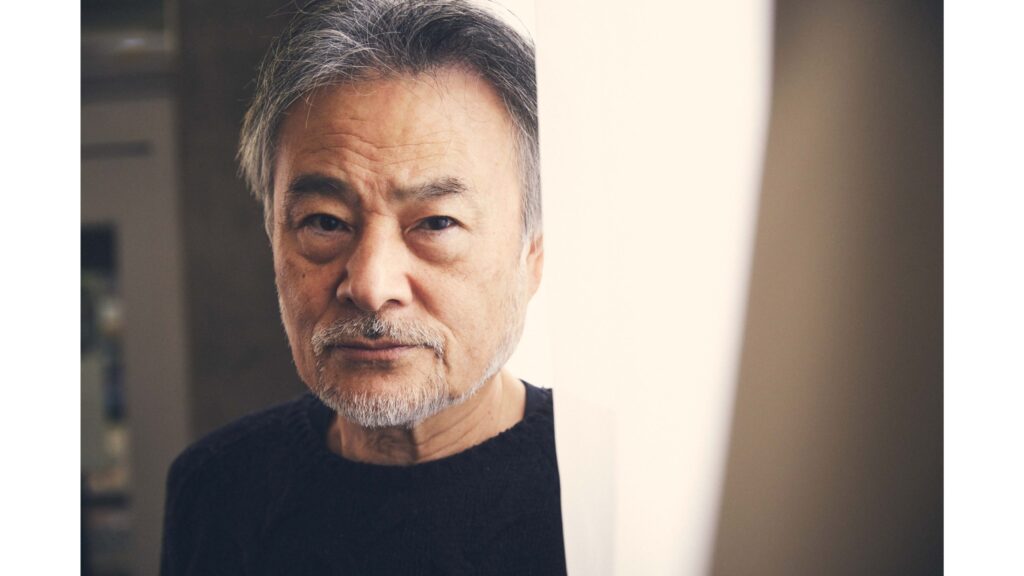

Who is Kiyoshi Kurosawa?

July 19, 1955

Japanese film director, screenwriter, film critic, and novelist.

In 1981, “Shikarami Gakuen” was selected for the Pia Film Festival. After working as an assistant director on a film directed by Shinji Somai, he made his feature film directorial debut with “Kandagawa Bawdan Senso” (1983). He won fans with such films as “Doremifa Musume no Koro ga Nogu” (85) and “Hell’s Guards” (91).

In 1992, he won a Sundance Institute scholarship for his original screenplay “Charisma” and went to the U.S. (the film was produced in 1999 and released in 2000). After returning to Japan, he worked on a series of films, including the “Jikkuri Shiyattegara! series (1995-96) starring Sho Aikawa.

In 1997, he attracted worldwide attention with “CURE”. Since then, “Circuit” (2001) and “Acalui Mirai” (2002) have been screened at the Cannes International Film Festival. He has made many horror films, including “Doppelganger” (2003), but he broke new ground with “Tokyo Sonata” (2008), a home drama that won the Jury Prize in the “Un Certain Regard” category at the Cannes Film Festival. His recent works include the serial drama “Atonement” (12) and the film “Real: The Day of the Perfect Dragon” (13).

In 2015, “Kishibe no Tabi” starring Tadanobu Asano and Eri Fukatsu won the Best Director Award in the “Un Certain Regard” category at the 68th Cannes International Film Festival. In the same year, he received the 33rd Kawakita Award.

In 2016, his first international film, “The Daguerreotype Woman” (original title: La Femme de la Plaque Argentique) was released. In the same year, he received the 29th Tokyo International Film Festival SAMURAI Award[30] and the 58th Mainichi Art Award.

In 2020 (2020), “The Spy’s Wife <The Movie>” won the Silver Lion for Best Director at the 77th Venice International Film Festival.

What is Jibaku-rei?

The following is the prevailing view of jibaku-rei.

Jibaku-rei are spirits who are said to remain in the land or building where they were at the time of their death because they cannot accept or understand that they are dead. Or, a spirit of the dead who is said to have a special reason to dwell in that land.

The term was coined by Toshiya Nakaoka, a leading figure in the psychic boom in Japan, and seems to have appeared in some Japanese language dictionaries in recent years. People who die suddenly in wars, accidents, disasters, etc. have a hard time accepting that they have died. Those who died with feelings of resentment or hatred are also affected by such bad feelings and cannot accept their death. Suicidal people also try to commit suicide again and again, realizing that they thought they were dead but in fact they are not. It is said that it takes months, years, or even centuries for these spirits to have an “awareness of death,” and until then, they remain near the earth as jibaku-rei.

Indeed, the Jibaku-rei in Kurosawa’s films seem to fit the above conditions. In some of his films, such a typical Jibaku-rei also appears. At the same time, however, there are also many Jibaku-rei that deviate from the standard mold. What kind of Jibaku-rei is this? Below is an analysis of Jibaku-rei’s actual works.

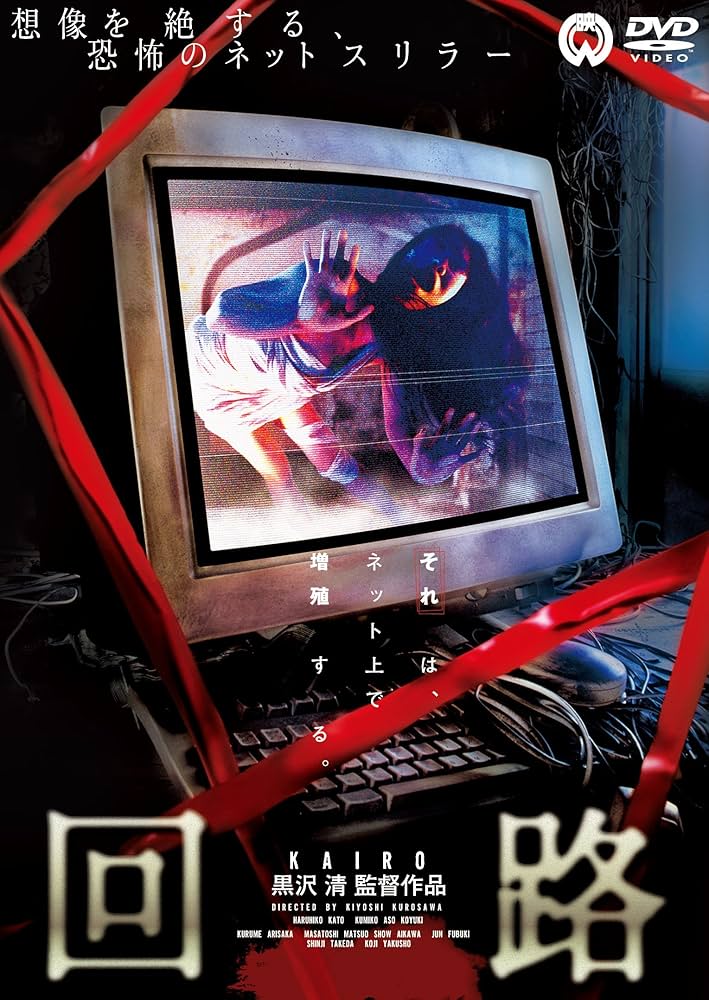

Jibaku-rei in “Kairo

This is a 2001 Japanese horror film. The synopsis is as follows

A strange website appears on the Internet. Are the figures appearing there departed souls wandering this world? …… Although there are few Hollywood-style shocking scenes, the dimly lit screen shot in natural light, the absurdity of the images and the story, with strange incidents happening around the main characters one after another without explanation, will send the audience into a state of unknown terror.

One after another, the characters are attacked by ghosts via the Internet and transformed into Jibaku-rei.

What was distinctive about this directorial expression was the depiction of the Jibaku-rei as “black stains. They are obsessed with “life,” and immediately after being attacked by the ghosts, they become stains, as if they were staying in that space. The stains look like human shadows and are horrifying.

There was one interesting line in the work. It was uttered by Karasawa, a character who is interested in ghosts on the Internet, in light of the series of disturbances in the case.

“Ghosts don’t kill people. On the contrary, they try to keep you alive forever. They keep you in solitude.”

These words came as a bolt from the blue in my own understanding of ghosts. Until now, the concept of ghosts had only existed in a cursory sense in my mind. Ghosts are the rightful owners of death and terrorize people, and sometimes, with their power that transcends vindictiveness and regret, they can bring about the death of the living. However, according to Karasawa, a character in the film, ghosts are rather the opposite. In the case of this film, ghosts are lured by people’s attachment to “life” and anchor their very existence to the wall. The obsession with “life” is merely an escape, a deviation from the natural flow of “death. That is why they cannot avoid the horrifying consequence of “black staining.

The instinctive avoidance of death, as in the case of plants and animals, and the human obsession with life are similar, but very different. We humans have conceptualized and shared “death” through our rationality. We have been taught by words, pictures, sounds, and images that there are as many deaths as there are living people, and that they come in various forms. Therefore, we always live in fear of death. We fantasize about the loneliness of “death,” and as if trying to drown it out, we cannot help but connect with others. Perhaps that is why Kurosawa included a setting of “a ghost inhabiting the Internet. The Internet is both a tool for propagating the concept of “death” and an ambivalent entity that provides us with a temporary communication.

In any case, the fear of death = the obsession with life is like a fetter given only to mankind, and the black stain = jibaku-rei in this film is, in other words, the excessive desire for life, and the lonely result of that desire. It is dirty, immobile, and simply stands there for eternity. Perhaps this is the message that Kiyoshi Kurosawa intended to convey with the character of Jibaku-rei. When I arrived at this interpretation, I felt that I had gained a new conception of hell, different from that of “death.

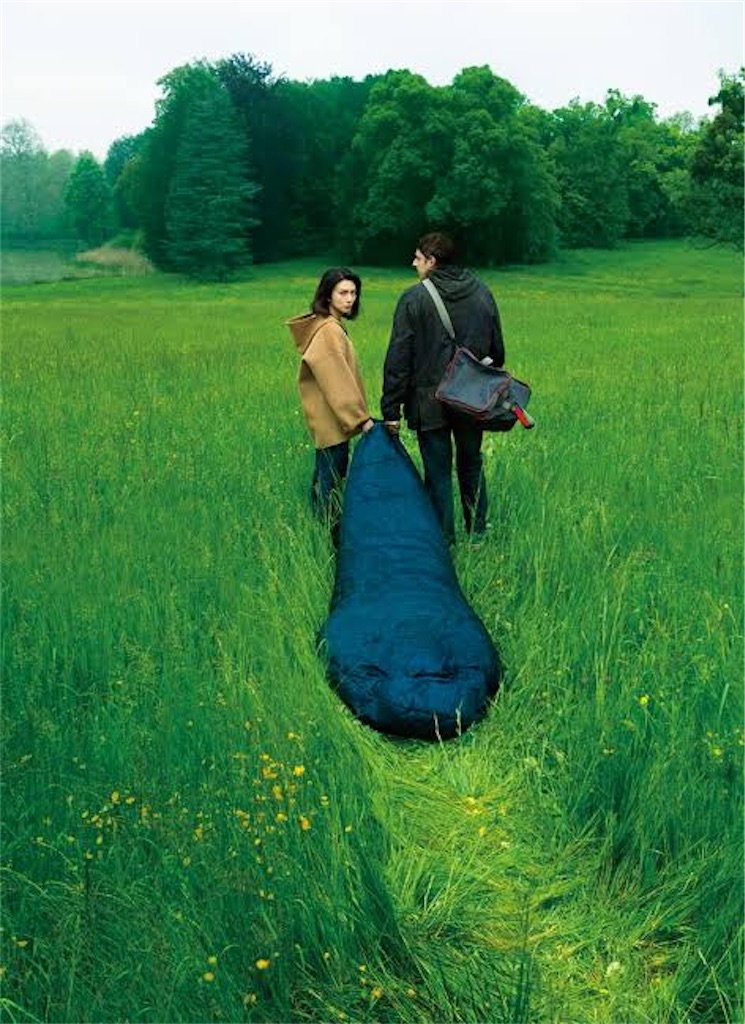

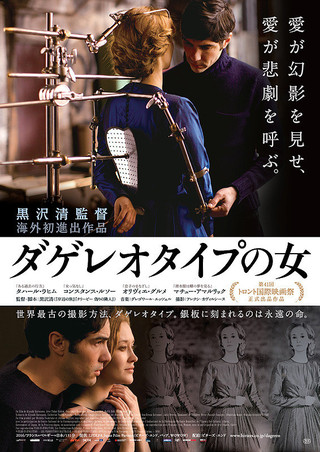

Jibaku-rei in “Daguerreotype woman

This 2016 French-Belgian-Japanese co-production is a romantic horror film. The story centers on the daguerreotype, a 170-year-old photographic technique, and the story follows Stéphane, a photographer who adheres to it, his daughter, and the main character, who is threatened by ghosts and love. Jibaku-rei in this film is the photographer’s wife. She was once the subject of a daguerreotype (an ancient photographic machine that immobilized a subject for several hours), which caused her to lose her mind and commit suicide (her husband, Stefan, even gave her muscle relaxants to immobilize her). After her death, she turned into Jibaku-rei out of resentment toward her husband and began to wander around the mansion.

Undeterred, however, Stéphane continued to photograph daguerreotypes, this time with his daughter as his subject. Of course, his daughter resisted and finally decided to move out. Unable to accept this, Stéphane pushes her down the stairs and kills her (I interpreted it that way, although it is not directly depicted that way). Having lost everything by his own hand, Stefan commits suicide, as if cursed by the ghost of his wife.

What is unique about this film is the fusion of the daguerreotype item and the Jibaku-rei. Photography is nothing but the desire to make a certain point in one’s life “stay forever,” which, like the characters who became Jibaku-rei in “Kairo,” is an obsession with “life” itself. The difference is that the subject is not oneself but others, and the “life” is arbitrarily cut off by the item of the daguerreotype = photographing machine. Photography exists only as the photographer’s ‘ideal form,’ i.e., a mass of egoism.” As I mentioned in the chapter on “Kairo,” the obsession with “life” is anti-natural, and it is outrageous to egoistically create an “ideal life” by using another person, even a close relative, such as a wife or daughter, as mere material. Mere escapism, deviating from the flow of nature, of course entails punishment.” As in the case of “Kairo,” the punishment was “black staining,” so in the case of “Daguerreotype woman,” the punishment was the jibaku-reiization/attack of a close relative.

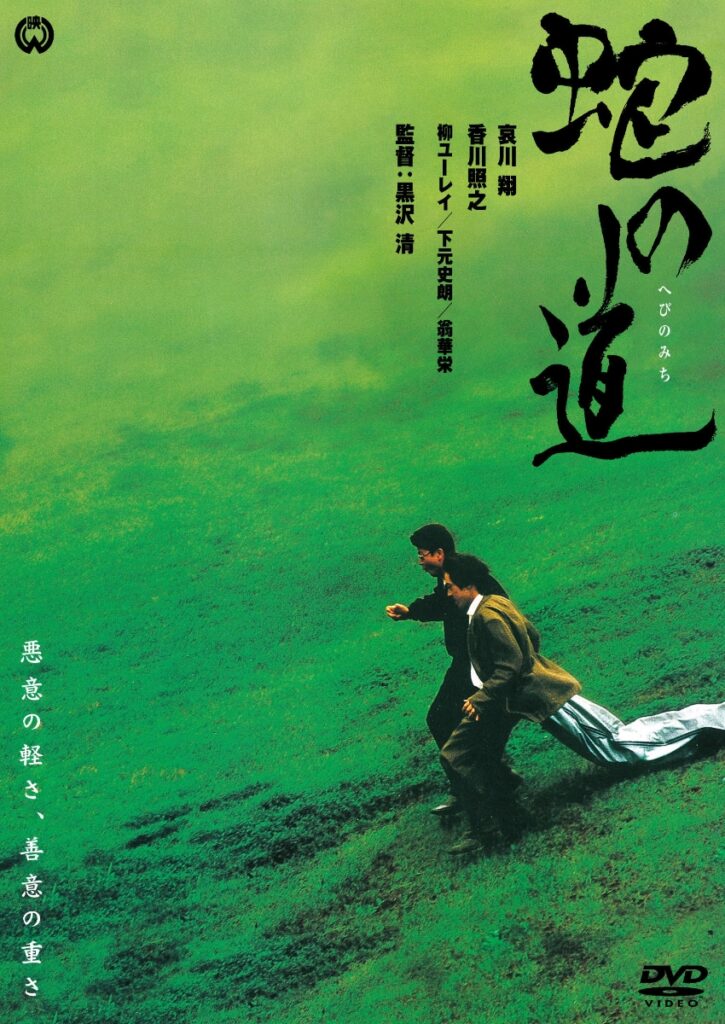

Jibaku-rei in “Serpent’s Path

1998. This violent drama depicts the revenge plot of a man whose young daughter was murdered and a mysterious man who helped him.

The protagonist, Miyashita, is searching for the murderer of his own daughter, and an unidentified man named Niijima (who usually works as a math tutor) helps him. He captures the yakuza and abducts and confines them in a warehouse, but they say that they are not the culprits. It is not clear until the end who the actual culprits were who laid a hand on Miyashita’s daughter, but the yakuza were actually filming and selling snuff films with their organization. Miyashita and Niijima kill the yakuza one after the other, and finally force them into their hideout. There, Niijima tells Miyashita, “My daughter was killed here, too. It turns out that Miyashita is actually a former member of the yakuza organization, and that he was a sales representative for the video. In other words, this story is Niijima’s revenge drama that includes Miyashita.

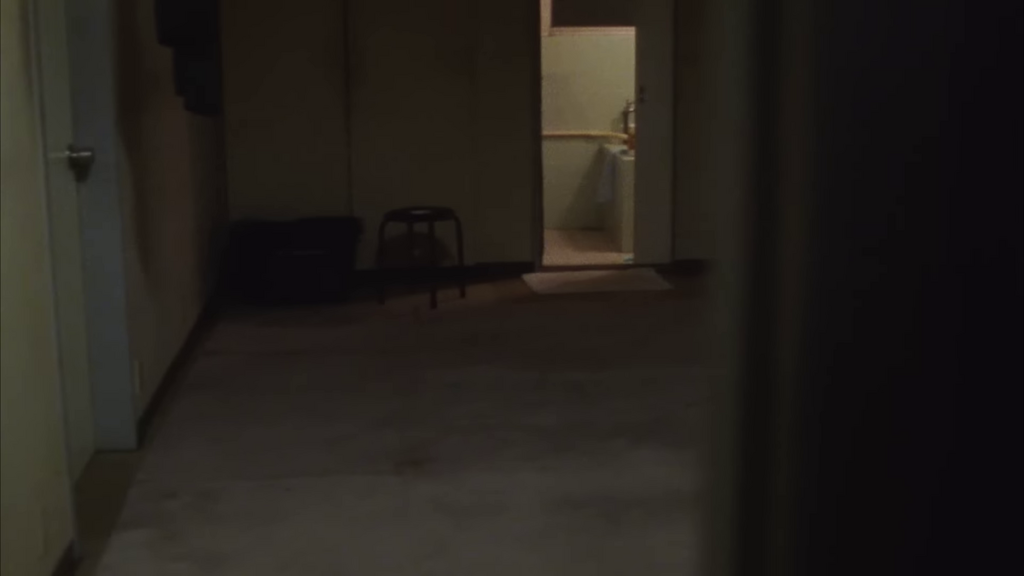

Unlike the above two works, Jibaku-rei itself does not appear in this work. Instead, the existence of Jibaku-rei is suggested by the “filming technique” without “appearing” as a character. The most obvious example is a scene in the confinement area. Yakuza Otsuki and Miyashita, who are handcuffed, are in separate rooms, and the camera moves autonomously to show them.

This image was taken after capturing the restrained Otsuki, and was moving to capture Miyashita in the background. The camera was probably handheld, and there is some camera shake. I found a blog post that analyzed this in detail (the author’s name was Nest). Below is an excerpt from it.

The camera turned its gaze away from Otsuki. It has cut it off. Taking into account the different nature of the two, one cannot help but perceive in the latter a willingness to abandon Ootsuki. Until now, the camera has implicitly asserted its autonomy, but the camera was only moving to follow the subject, moving along the line of motion. This shot, however, is the result of the camera actively moving to capture two people whose positions are unchanging, Otsuki and Miyashita, in the same shot. More than just autonomous and more than just physical, they are human in the sense that they have a will. The camera moves on its own, not on behalf of anyone else. The camera, an inorganic mechanism that should not exist in the world of the story, takes on a principle of action separate from that of the characters and the audience. The camera captures this shivering moment as an image. It is placed in a different phase from the horror of the eerily gloating Miyashita. The spectator is unable to connect or reduce the horror of this grounded camera behavior to anything. This is because the camera, which has become autonomous, has ceased to be a passive recording device or a human surrogate. And yet, there are indeed “legs,” as indicated by the oscillations imprinted on the images. As mentioned above, what can be accomplished when Otsuki complains of bowel movements to the elusive camera? The camera is merely there, and it will not release Ootsuki from her restraints, nor will it encourage Miyashita to temporarily release her. The camera, positioned between Otsuki and Miyashita, is not a mediator, but an autonomous third-party presence, a machine without words. The camera has only the cruelty of a stranger, abandoning Ootsuki, who continues to appeal to the camera, and turning its curiosity on the strange Miyashita. Ootsuki is tormented by a double sense of alienation, as she feels unresponsive to both Miyashita and the camera. In this way, Ootsuki’s fear of confinement – of being left out and ignored – is expressed from the perspective of the abandoner. The audience has no way to interfere with the camera’s cruel treatment of Ootsuki, but can only witness it. The audience, too, is horrified and horrified by the fact that they are being shown this bizarre situation without a care in the world.

When I finished reading this discourse, I was convinced that this was the cause of that unverbalizable eeriness I felt when I saw the film.

The author of this article, Nest, is also so definitive because he has clearly seen that the filmmaker/director uses different camera movements for different scenes, and that this “camera in autonomous motion” is intentionally incorporated into the film. As evidence of this, for example, scenes that merely explain the situation are all done with a fixed camera and inorganic slides.

And filmmaker Yusuke Sasaki calls the shaky images “Jibaku-rei.

Jibaku-rei’s images are shaky hand-held camera images, so naturally they do not rely on the mechanism of a tripod. The camerawork is based on the structure of the filmmaker’s body, including the rotation of the torso and the range of motion of the arms. Furthermore, for Jibaku-rei’s images, a fixed camera is neither a prerequisite nor an exception. In the beginning, there is a camera that sways. Jibaku-rei’s images inhabit the film of a “shaking camera.

In other words, the Jibaku-rei in “Serpent’s Path” was the camera. During the viewing of the film, I remember feeling a mixture of unease and frustration at the repeated “shaking” of the images, which made me feel uncomfortable. However, since nothing of the sort had happened, the feelings were suppressed in my subconscious and my brain simply followed the narrative exchange in front of me. In reality, however, I probably felt some kind of “will” in the camera, but it was the way the camera abandoned the tortured Ootsuki that made me feel unbearably uncomfortable.

The next question is, then, who is this Jibaku-rei? My guess is that it is the people Niijima has killed so far. Perhaps Niijima has killed someone in that warehouse before. Otherwise, he was too skilled in the task of murder. For a mere cram school teacher, he was too deft and, above all, too calm and collected. And since he himself was in the position of having had his daughter killed by the yakuza, it is not surprising that he had been committing murders as part of his revenge. As for the person who was killed, he may have been involved in the production and sale of the snuff film. Also, Niijima still speaks in a way that could not be said without having encountered a similar situation, such as when he refers to a warehouse in the confinement area and asserts, “Voices in here cannot be heard outside.

The criminals who were killed by Niijima cannot hold a grudge (he is the one who caused the death of Niijima’s daughter), and nihilistically watch his murder show unfold again and again. Or perhaps they are even looking at him as if to say, “Hurry up and come over here.

Jibaku-rei for Kiyoshi Kurosawa

Why does he go to such lengths to continue painting Jibaku-rei?

One of the first reasons is that it presents a certain philosophy of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s. As mentioned above, I think he probably considers the human obsession with “life” to be the most vulgar spirit of all.

For example, in his film “Spider’s Eyes,” there is a yakuza boss who works as a fossil miner, and he says of fossils, “These people have found a new way of life.

He says of fossils,

“These guys have found a new way of life.”

“Emptiness is not misery!”

But he is eventually betrayed and killed after this. He was shot to death in the mining area with a pistol, a brutal end. The reason I included this description was to send a critical message to the spirit of this yakuza mastermind. The fossil is, perhaps, nothing more than an adherence to “life” from the viewpoint of Kiyoshi Kurosawa. All life must accept “death” and return to the earth. In “Spider’s Eyes,” a man whom the protagonist had supposedly killed and buried in the ground appears at the end of the film in a wheelchair. When the protagonist rushes to see where he was buried, he finds a mark as if he had crawled out of a hole. In that last part, the man is in a wheelchair with a damaged spinal cord or something, and is being carried by a woman, but his eyes are vacant. We don’t even know if he is conscious or not. The scene is quite gruesome and painful. It may be that Kurosawa, too, has fallen into nihilism due to his fixation on “life,” instead of returning to the earth.

In other words, Kurosawa criticizes the fixation on “life” through his own works and introduces Jibaku-rei, the “worst possible landing place,” as an item to convey this message.

Another reason why he paints Jibaku-rei, I believe, is because he considers “anxiety” to be the most universal emotion that exists in humankind.

The act of “living” means “going toward death,” and anxiety is always present. Sometimes, people can make their “anxiety” disappear by encountering joy, love, pleasure, and other such emotions. Still, at the root lies the unquenchable feeling of anxiety that one day one will eventually die. I believe that this feeling arises because of the foresight that only humans possess, which allows us to conceptualize death and apply it to our own “future.

What is also interesting is that this conceptualization and foreknowledge allows us to make “the exact opposite” assumption. That is.

“What if I can’t die forever?”

There are many stories about immortality, but have any of them ever been depicted in a positive light? In the ancient Mesopotamian literary work “The Epic of Gilgamesh,” a woman who owns a liquor store tells Gilgamesh, who is pursuing immortality, that he will not be happy even if he becomes immortal. In the Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, Kaguyahime weeps, saying that she “loses her heart.” Because “time” has no value, we can no longer find meaning in our every move we make (we only have a few decades left, which is why we are still trying to do our best today). There is only emptiness.

Fear of death and a sense of emptiness about immortality, or eternal life. I think the word “anxiety” encapsulates both of these two similar but different feelings and concepts. And I believe that this “anxiety” is the most fundamental thing of human beings and the principle of all actions.

This is why I think Kurosawa sublimates these two emotions with the existence of Jibaku-rei, an entity that simultaneously undertakes death and immortality. Jibaku-rei is an ambivalent being who cannot die even after death, and is a frightening character who makes people feel fear and emptiness, and brings to the surface at once the concept of “anxiety” that lies dormant in their unconsciousness.

★This blog’s writer: Ricky★

Leave all your cultural needs to us! Ricky, the evangelist of Japanese culture, will turn you into a Japan otaku!

Source

黒沢清 Wikipedia

・https://note.com/art_critique/n/n598c1eb6e87e

・https://nsthtn.hatenablog.com/entry/2024/06/16/155500