An ordinary residential area. A group of adults surrounded a certain facility. From the way they are dressed, they seem to be ordinary residents of the neighborhood. They stand as a monolith around the facility like a solid wall. It was neither curiosity nor onlookers’ guts that incited them. It is the mobilization of negative emotions such as discomfort, righteous indignation, hatred, and so on.

And it is heading toward something inside the facility. And yet, as if there were some kind of barrier, they are holding back, showing no sign of approaching us, not even a single step, from the invisible boundary line.

The camera filmed this scene from the side of the facility. The hand-held camera makes their gazes seem even more realistic, and we, the viewers, are under the illusion that they are directed at us. We feel uncomfortable and are tempted to run away right away.

This is not a fictional image. It is a scene from a documentary film. Nothing dramatic is happening, but as a college student at the time, I remember that watching this scene brought up feelings I had never experienced before. Faces, faces, faces of city people everywhere, driven by hatred…. I was enveloped by a blurred feeling that I could not verbalize.

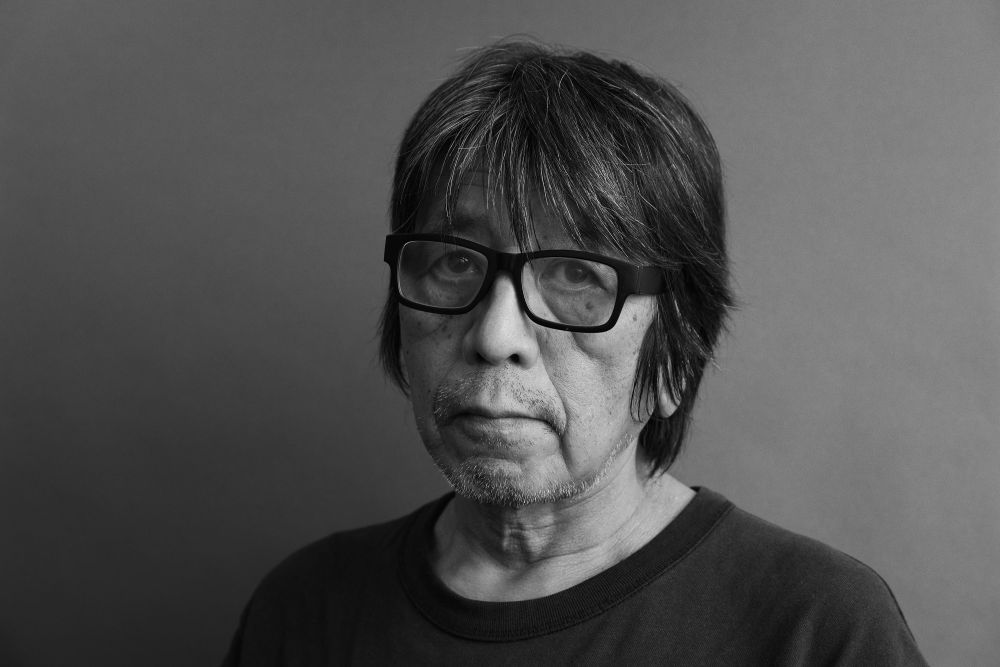

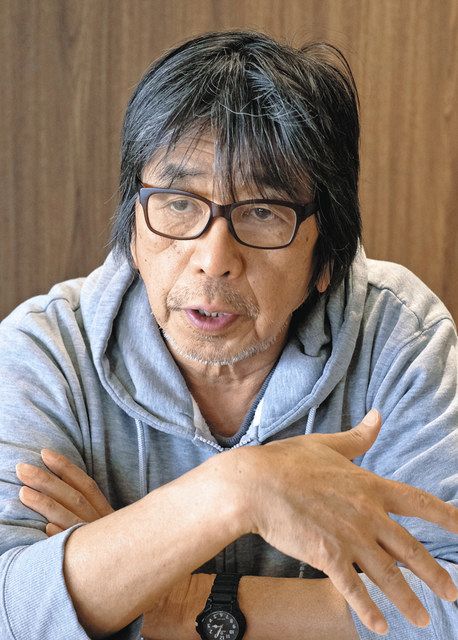

Mori Tatsuya, the director of the film “A,” was my mentor during my college days.

“I guess you will continue to create something like that.”

I remember as if it were only yesterday that a red-faced Tatsuya Mori said this to me at a Taiwanese restaurant in Ochanomizu nearly 10 years ago. It was a few years after graduation when we got together for an alumni meeting or something. I think it was something he said when we were reporting on the progress of a novel or a comic book or something we were working on at the time. He was well into his drinking and must have forgotten what he said, but at least his smile and his words were full of compassion, which is the reason I have been able to continue my creative activities even though I am not very good at them. Thanks to him, I have learned about the multifaceted nature of human beings, their arbitrariness, and their ferociousness when grouped together. The influence that this has had on my own creative expression, including the writing of this blog, is immeasurable.

In this article, I would like to introduce the achievements of this rare filmmaker, Tatsuya Mori, and explain why he continues to film taboo subjects, as well as the true nature of human beings as depicted in his bizarre work “A.” In order to do so, it is necessary to go back to the limits of my memory to retrieve the gems of words that Mori conveyed to us on that day, on that campus. This will probably be a personal journey of memory for me.

Who is Tatsuya Mori?

Tatsuya Mori (born May 10, 1956) is a Japanese documentary director, television documentary director, nonfiction writer, and novelist.

He made his debut in 1992 with “Midget Pro Wrestling Legend: Small Giants,” a TV documentary on midget wrestling.

A”, a documentary film that follows the daily lives of Aum Shinrikyo followers, centered on Hiroshi Araki, Deputy Director of Public Relations. In 2001, he released a sequel, A2. It premiered at the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, where it won the Citizen’s Prize and the Jury Prize.

On the other hand, in television, he has made several films for Fuji Television’s “NONFIX” slot, including “Shokugyo Ran wa Esper” (1998), which captured the daily lives of those who work as espers, including Masato Akiyama, Yuji Tsutsumi, and Masuaki Kiyota; “1999 no Yodaka no Hoshi” (1999), which depicted the contradiction of humans living at the expense of other living things; “Hoso Boku Uta” (“Hoso Boku Uta” – Who is singing? Who is singing? Who is regulating it? 〜(1999), which depicts the contradictions of people living at the expense of others.

In 2014, he decided to make a film about the “ghostwriter issue” of Mamoru Samuragochi, which caused a nationwide uproar.

In 2023, “The Fukuda Incident” won the Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Screenplay awards at the 47th Japan Academy Awards, the 41st Golden Gross Award, and second place in the Kinema Junpo Readers’ Choice Ten Best Japanese Films.

Characteristics of Tatsuya Mori

Mori is a filmmaker who always challenges taboos. Cult religions, the physically disabled, the death penalty, nuclear power plants, the discriminated Buraku…

(The Fukuda Village Incident, released last year, was screened nationwide for the first time in almost all theaters.)

Let’s take a look back at what kind of films he has made so far.

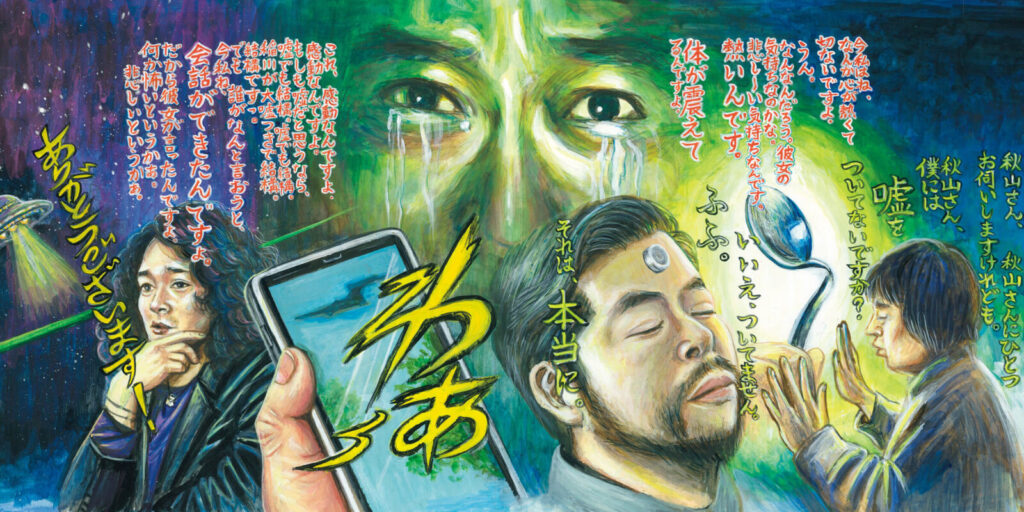

・”The Occupation Column is Esper” (1998)

This short documentary explores the mentality of three psychics who have made it their profession to be espers through their daily lives, and was produced and broadcast for the CX late-night program “NONFIX.

All of them became TV stars during the occult boom, but gradually these programs changed to “exposing the frauds of psychics,” and the espers were called frauds. In addition, some people began to take advantage of their psychic performances to join cults and pyramid schemes, while others were labeled as “insane. Esper had gradually entered the realm of “taboo.

Mori closely follows the three psychics and captures their anguish and disconnection from the world with his hand-held camera. They also perform dowsing, telekinesis, and spoon bending as a matter of course. Still, Mori says to them, “I recognize the phenomena before my eyes, but I still don’t believe in psychic powers. Kiyota, one of the psychics, replies to Mori, “I don’t believe in ESP.

“I think you can be kinder to people if you are a little more interested in things like human potential and manifestations of the mind, rather than psychic powers.”

More than 10 years ago, this video was discussed in a seminar class. As a student, I once cheekily asked Mori the following question.

“Sensei, the psychic power in that video was actually a fake, wasn’t it? Please tell me the truth.”

For my part, what I was hoping for in Mori’s response was a revelation from someone who knew the other side of the story, that their performance was in fact a sham, with a wry smile and a “well, actually…”.

But the actual forest seemed to have nothing to say to my choking question.

“No, psychic powers do exist. I have seen it many times.”

I have seen it many times,” he replied matter-of-factly. It was as if he was saying, “I don’t really care if I have ESP or not,” and I remember being puzzled. I was a mere greenhorn, so I could not have any impression of this work, “The Occupation Column is Esper,” other than the question, “Does ESP exist or not? I was only interested in “making things black and white,” and I could not imagine the intention of the production and the message of this work, which took up the “taboo” of psychics and showed the drama of the people surrounding them.

・”FAKE”(2016)

A Japanese documentary film produced in 2016. This documentary film follows Mamoru Samurakouchi, who has been in the middle of a ghostwriting scandal for a year and four months, as well as TV people who interview him and foreign journalists who come to confirm the truth of his story.

Mamoru Samurakawachi, a musician who composed “Symphony No. 1 “HIROSHIMA” and other works despite his hearing impairment, was once hailed as a modern-day Beethoven. However, in 2014, he became the target of accusations in a weekly magazine that he did not compose music and that he is actually deaf. Composer Takashi Aragaki, who served as a ghostwriter, claimed in the weekly magazine that Samuragochi had lied about being totally deaf for 18 years and that he could not compose music or even play an instrument. Although Samuragochi subsequently held an apology press conference, his brusque attitude at the scene and behavior that made it appear as if he was able to respond to reporters’ questions led to criticisms such as “He has no remorse” and “You can still hear me,” which blew up on wide shows and social networking sites.

The film was shot mainly at Samuragochi’s home in Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture, between September 2014 and January 2016, when such public interest had gradually waned. A hand-held camera, a specialty of the film, shows the lives of the two transformed by the ghostwriter scandal. The film continues with the heavy atmosphere of the Samurakawachi household, with its damp atmosphere and gloomy expressions. On the other hand, the film’s heartwarming images are hilarious, such as the overweight cat (director Tetsuaki Matsue described the film as “a film from the cat’s point of view”), the cake that is always distributed for some reason, and Samurakouchi gulping down soy milk. The film also shakes the audience with its turbulence, as in the case of the visit to Niigaki, the ghostwriter of the story.

However, this film is by no means about “proving Samuragochi’s innocence. The public’s interest in Samuragochi was based solely on a desire to “find out the truth,” such as whether he could really compose music and whether he could play an instrument. As if to counterbalance these expectations, Mori does not provide easy answers. For example, in the last scene, Samuragochi himself plays a piece he composed on an electronic piano, but it is impossible for the layman to tell whether his performance is in fact anything more than that of an amateur. The written instructions for the music captured by the camera also do not prove the composer’s ability to compose. There is a scene in the film in which Mori asks Samuragochi,

“Is there anything you are hiding from me?”

Samuragochi could not answer this question immediately. He has spent so much time with Mori, with whom he has talked about everything thoroughly, that he still has something to hide? And Samuragochi, who had publicly confessed at a previous press conference that he had returned his disability certificate, had nothing more to hide. But when Mori asked him a question earlier, Samuragochi looked away. The film ends with the same ambiguous atmosphere. The audience leaves the theater with an impatient feeling. It is as if they were the reporters who questioned Samurakawachi at the press conference. The feeling of indigestion swirls around me, as if I want to make the issue black and white.

“Is he a liar after all? Which is it?

Incidentally, at the time, the first thing that came to my mind after watching the movie was

I thought, “By the way, there was a time when he didn’t come to the university at all, but it might have been because he was filming this movie.”

In “Esper”, “FAKE”, and his various other works, his subjects are people who have been marginalized, belittled, and even “tabooed” by the public. Why does he always use such “taboo” subjects in his films? It is a difficult subject for him to cover, and he must have suffered at the box-office every time because of it. In the case of “A,” the film was completely in the red. So why does he continue to challenge the “taboo” with an attitude that could be called stubborn?

Perhaps the answer has already been given by “A,” his film debut. I would like to explain the reason for this in the following paragraphs.

Representative work “A”

A” (A) is a 1998 Japanese documentary film directed by Tatsuya Mori. Focusing on Hiroshi Araki, the deputy director of public relations for Aum Shinrikyo, the film captures his relationship with society, and was screened at the Berlin International Film Festival, as well as film festivals in Hong Kong, Pusan, Beirut, Vancouver, and other countries. The title “A” is said to derive from the A in Araki and A in Aum.

It is a rare film that shows society’s attitude toward Aum Shinrikyo since the sarin gas attack on the subway, from inside Aum. The film shows the training and daily life of Aum believers, news reporters pointing microphones and cameras at Araki, and police officers forcibly arresting Aum believers.

The unprecedented act of spraying nerve gas on the subway caused a public panic. The perpetrators were caught, but their organization, Aum, was not immune from the public’s fear, hatred, and other emotions. The news media flooded their facilities, and nightly news reports showed images of their followers.

Mori, a freelance video director at the time, succeeded in infiltrating the Aum facility. The film’s camera captured a lineup of bizarre yoga-like exercises, strange food, and headgear that emitted electromagnetic waves, all of which were dubious and very cult-like in nature. The essence of the film, however, lies not only in the capturing of such stimulating objects.

First of all, what is interesting about this film is that the subjects are not only “Aum” but also “the world. Their facilities, which were recognized as a cult and impeached as a criminal organization, were monitored 24 hours a day by the police, right-wing groups, and residents. Their followers were not allowed to casually go out into the city. Although they belonged to the Aum organization, most of them were merely practicing their faith. The majority of them had never heard of the sarin gas attack until they saw it on TV. However, the world did not care about such circumstances. The victims and those involved in the case seem to be the obvious ones, but even those not directly involved in the case were inclined to Aum bashing and became monolithic, threatening their daily lives, not to mention their practice of Buddhism. And perhaps this is where Mori saw the value of documentary film. So he went out of his way to send a letter in person to the Aum public relations department, asking them to let him film the Aum from the inside. This was an approach that no other TV station’s press corps had even thought of. In doing so, he completed an unprecedented documentary film that turned the camera from the inside of a cult to the outside. The content of the film is so bewildering that it raises a question mark over the absolute dichotomy of Aum as the strong and evil, and the citizens as the weak and good.

Having thus provided a brief introduction to “A,” a film that marks a Copernican turn in our understanding of the sarin gas attack, it still seems that the question of why Mori dealt with the “taboo” of Aum remains unanswered.

I think that Haruki Murakami’s famous speech could be the key to solving this mystery.

・Haruki Murakami’s “The Wall and the Egg” speech

This is a speech that Haruki Murakami gave at the award ceremony held in Jerusalem on February 15, 2009. It used the metaphor of “walls and eggs,” which caused a great stir at the time. Below is an excerpt from the speech.

If there is a big, solid wall here and an egg that hits it and breaks, I will always stand on the side of the egg.

Yes, no matter how right the wall is and how wrong the egg is, I will still stand on the side of the egg. Right or wrong is something that someone else decides. Or it is something that time or history decides. If a novelist, for whatever reason, wrote a work standing on the side of a wall, how much value would that writer have?

So, what does this metaphor mean? In some cases, it is simple and clear. Bombers, tanks, rockets, white phosphorus shells, and machine guns are big, solid walls. Unarmed civilians who are crushed, burned, and penetrated by them are the eggs. That is one meaning of this metaphor.

Now that I think about it, Murakami’s works always feature weak people as protagonists, and mysterious entities and organizations that persecute them. The conflict may indeed be similar to the relationship between the wall and the egg. What would happen if we were to substitute this for the case of “A”? Without a doubt, the egg would represent the innocent Aum followers, and the wall would represent the press and society that denounce them. But is that really all there is to it? Is the social climate surrounding Aum once again made up of such a simple binary opposition? Mori probably didn’t think so.

・The moment an egg becomes a wall

In terms of understanding the concept of a “wall,” Mori Tatsuya surpasses Murakami Haruki in the possibility that “any egg can become a wall.” Look back at “Occupation: Esper” and “FAKE.” The people who condemned psychics and composers were harmless ordinary citizens. These people, who are usually good-natured, once they recognize an object as something (…), they go through stages of ignoring, treating it coldly, and finally begin to persecute it. That something (…) is the very concept of “taboo.” Dwarf wrestling, discriminated communities, refugee issues… Humans are creatures who easily recognize things that should be naturally present around them as “taboo” based on extremely arbitrary standards of judgment. And the moment that recognition is approved by a large number of people, those who agree turn into a mob that confronts that “taboo.” The same is true of Aum. The local residents had probably already recognized the Aum facility, which had always been a thorn in their side, as a “taboo.” However, they only responded by ignoring and treating it coldly, reluctantly following the constitutional freedom of belief. Then, with the Sarin gas attack, they finally stepped up to persecution, intervening in the facility and even campaigning for its eviction. And, of course, it was the good local residents who were leading the charge. They were supposed to be good fathers and mothers when they returned home, but as soon as they stepped in front of the Aum facility, they turned demonic and persecuted the innocent believers.

In other words, Mori has been depicting, from his debut to “FAKE” (in fact, the same structure is used in his latest work, “The Fukuda Village Incident,” but I will not go into detail in this blog because it will take too long), how by adopting the concept of “taboo,” any “egg” can become a “wall” the moment it is recognized as a taboo. Mori has taken a stance on his artwork policy that could be described as one-sided, but what has continued to motivate him? Is it social indignation or a personal sense of justice? Don’t underestimate him. What has driven him to create his works thus far has never been based on such petty moral sentiments.

・Funny “walls and eggs”

There is a movie called “A2” (2001) that is a sequel to “A”. The followers of Aum Shinrikyo, who changed their name to Aleph and continue their activities in place of the bankrupt Aum Shinrikyo, are depicted in the movie. The movie depicts the conflict between the followers and the local residents, the outcome of the suspected assault and confinement case that triggered the enactment of the Association Control Law, and the discrepancy between the intentions of right-wing demonstrations and the media reports.

There is a very strange scene in this movie.

A “strange relationship” was born between the followers and the residents who tried to expel the followers. The residents built a tent hut and kept watch in an attempt to expel the followers, but after talking to the followers through the wall, they ended up becoming friends with them. They were not persuaded by the followers. When I talked to the followers who had given up their desires and lived as monks, I found that they were unexpectedly serious, spoke politely, and were not scary at all. Residents even went so far as to tell the followers, “If you leave the group, come and see me.” In the end, the tents and prefabricated buildings used to monitor the followers were dismantled, with the cooperation of none other than the followers themselves. On the last day, the residents who were monitoring and the followers who were being monitored took a commemorative photo with a “Stop Aum at all costs” sign in the middle. Even after the monitoring hut was dismantled, the residents and followers continued to interact over the fence. One male resident, concerned about the situation with the police’s forced searches, visited the facility over the fence many times and laughed, “The group that monitored the followers has become the group that protects them, ha ha.”

A few years ago, I went to see this film at a theater where it was shown again, and the audience burst into laughter at this scene. This is probably what Mori Tatsuya wanted to portray.

The tone has changed a little since the beginning. In the previous paragraph, I think I introduced the main text by saying, “From Mori Tatsuya, I learned about the multifaceted nature of human beings, their arbitrariness, and their ferocity when they form groups.” However, as I continued writing about him and his work, I began to feel that his philosophy was somehow deeper than that. I will summarize it again below.

When a person sees a “taboo,” they transform from an “egg” into a “wall.” A person who was a weak victim until just now transforms into a violent perpetrator overnight. However, in reality, the “wall,” which appears cold, merciless, and solid, is still completely human. It remains as arbitrary and extremely unreliable as ever. The next day, you can even take a friendly commemorative photo with someone you ostracized the day before. That’s how ridiculous the “wall and egg” issue is. It’s important to realize how ridiculous this is. On which side of the “wall and egg” are we on right now, and how well-founded is that? If you stop and think about it, and feel absurd and relaxed by the baseless difference, there will be no good or evil there. If you don’t realize that it’s ridiculous and push forward with it due to peer pressure, I think war is probably what lies ahead.

Mori Tatsuya exposes the helpless nature of such people, a kind of historical fate, from the perspective of “taboo”. However, it is by no means due to some desperate sense of justice driven by righteous indignation. Rather, you can even see an attitude of looking at the subject with a smile. If you watch the movie, you’ll understand. You can see that Mori, holding the camera, cannot hide his smile even through the footage. I mentioned earlier that film director Matsue described “FAKE” as “a film from a cat’s point of view.” In response to this, I suddenly thought that Mori Tatsuya is the very cat in Natsume Soseki’s “I Am a Cat.” He is probably always looking at humanity from a cat’s point of view. He is looking down from atop a wall at the writhing of living beings. And the humorous and endearing world seen through the eyes of such a cat is probably “A,” “My Occupation is Esper,” and “FAKE.”

Conclusion

Thinking back on it now, maybe the smile he showed me at that Taiwanese restaurant was also a cat-like attitude. I think he felt kindness, pity, and even a sense of humor surrounding me, because even after becoming a working adult, I still wander around and spend my time reading manga and novels, and that’s why he spoke to me like that. But I don’t think he made fun of me at all. He is a man who has dedicated his life to turning “The Wall and the Egg” into a film. The reason he was able to achieve this is because he must have felt love for his subjects. So, as one of Mori Tatsuya’s beloved disciples, I intend to continue to devote myself to spreading awareness of his work.

★Writer of this blog: Ricky★

Leave all things cultural to me! Ricky, the evangelist of Japanese culture, will turn you into a Japan otaku!

Sources

・Tatsuya Mori Wikipedia

・Yasuyuki Okamura x Tetsuya Matsue: Director Tatsuya Mori’s first documentary film in 15 years talks in detail about “FAKE,” starring Mamoru Samuragochi, Part 2