I would like to talk about a certain movie. The main characters are Komachi and Kodama (named after the Shinkansen bullet train), young men who love trains. Both are timid but gentle young men who enjoy sightseeing by train on their days off, and both are shy about romance, typical of geeks. The two meet through the railroad, and their work and romance develop around the railroad. I would like to introduce a scene from the film.

The main character, Komachi, comes to work at the office. His female colleague, who likes him, rushes up to him. She secretly overhears him and tells him, “I have a good property available. They are real estate developers, and they know the trends of good properties.

Komachi was in a situation where he had recently lost his place of residence due to the dilapidation of the apartment he was living in. Being the type of train geek who enjoys scenery, he was not interested in that apartment with its convenient access to the subway. The conversation ends without much progress, and the two walk away from the camera. It is an ordinary, everyday scene that can be found anywhere.

However, despite such a scene, the viewer loses focus on the exchange between the two. This is because something is unfolding in the background of their exchange, and their eyes are drawn to it.

Behind them, near the entrance of the office, two men are struggling with each other. A black security guard is pinning what appears to be a customer who complains a lot down and trying to remove him from the office. The security guard is using his size to pick up the man and remove him from the office, but no one can hear either of them. It is bizarre because it is captured on the screen at the same time as the aforementioned exchange of property. We are puzzled, laughing at the lack of context and wondering what in the world we are being shown.

This kind of direction is, in the textbook sense of filmmaking, absolutely not legal. When depicting a certain scene, the first principle should be “to eliminate extraneous information,” and background props, extras, lighting, music, and everything else should exist only for that scene.Of course, that principle should also apply to this film. Moreover, their aforementioned conversation is an important scene in terms of the future development of the film, and the audience would normally be asked to concentrate on their interaction.

In this film, however, the filmmakers easily break such principles and provide the audience with a chaos of discomfort in a fair and honest manner. The film is called “Bokutachi Kyuko A-Train de Ikirou” (Let’s Go on the express A Train), directed by Yoshimitsu Morita.

Morita’s films are full of this kind of direction. This is his originality, and it has made him famous as a master of comedy films, but I have always wondered why. Like in other comedies, there are no obvious gags or deviations, but rather Morita simply depicts ordinary everyday life as described above. However, the “setting” is so strange that it makes us feel uncomfortable, and we laugh at it.

What is the reason for this sense of discomfort?

And is this discomfort the only reason for our laughter?

And what is Morita’s intention in this production?

In this article, I would like to solve this mystery. In order to do so, I will employ the “Shasei-bun,” a form of written expression, as a tool, albeit in a somewhat acrobatic way. I would also like to approach the thought of Soseki Natsume, a rare writer who innovated the concept of “Shasei-bun”.

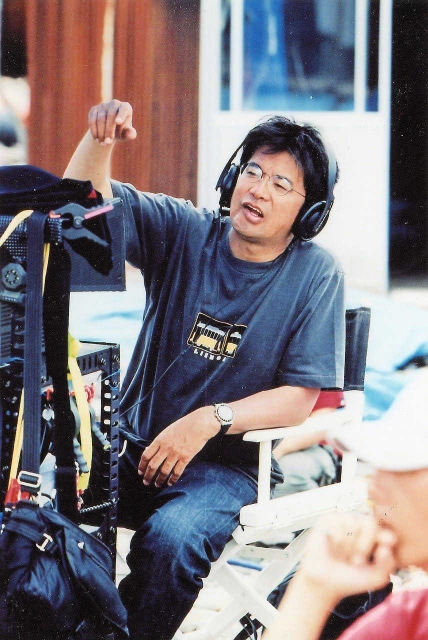

Brief introduction of Yoshimitsu Morita

Yoshimitsu Morita (January 25, 1950 – December 20, 2011) was a Japanese film director and screenwriter. He ambitiously handled a wide range of themes from serious dramas, comedies, black comedies, idol films, romantic films, horror films, and mystery films, and produced many topical works.

In 1981, he made his debut with “No. Like” featuring a young rakugo storyteller, which he produced with a mortgage on his parents’ house.

In 1983, he released “The Family Game” starring Yusaku Matsuda. It was a remarkable black comedy that cynically and violently depicted a family, and was well received for its cannibalistic direction that portrayed ordinary everyday scenes in an extraordinary manner. It won many major film awards in the same year, including first place in the Kinema Junpo Top Ten, a major leap forward from his previous work, which had received only partial acclaim, and attracted widespread attention as a genius of the new generation.

In 1984, after “Death to Tokimeki” written by Kenji Maruyama and starring Kenji Sawada, “Main Theme” starring Hiroko Yakushimaru became a big hit.

In 1985, the film adaptation of Soseki Natsume’s “Sorekara” starring Yusaku Matsuda followed. Once again, the film dominated the major film awards that year, and, unlike his previous unorthodox works, it was a prestigious literary epic that further enhanced his position in the film industry by demonstrating his breadth of experience.

In the first half of the 1990s, he took a short break from the world of film, giving priority to activities such as scenario writing and writing serialized essays on horse racing.

In May 1997, he adapted Junichi Watanabe’s “Shitsurakuen” into a film starring Koji Yakusho and Hitomi Kuroki. The story of a middle-aged man and woman, tired of life, who end up having an affair and end up having a heart-to-heart, was designated R-15. As a result, the film became a blockbuster hit with an audience of over 2 million, and the term “Shitsurakuen (Paradise Lost)” was named the year’s most popular word.

He died of acute liver failure due to hepatitis C on December 20, 2011 at the age of 61.

Shasei-bun-like Morita Films / Similarity to Natsume Soseki

・Shasei-bun and the discomfort of “Then”

Morita has made films in a variety of genres, but one of the characteristics of his work is his exceptional sense of comedy.In particular, his sense of comedy shines through in films such as “No, What Like,” “Sorekara,” and ” Let’s go on the express A train”. However, it has already been explained in the previous section that these films are not always funny in the sense of easy-to-understand gags or exaggerated deviations by the characters.

One more concrete example is a scene from “Sorekara”. The film, oddly enough, is based on the novel by Soseki Natsume, and tells the story of the protagonist Yosuke, a rich slacker, who falls in love with his best friend’s wife and is caught between ethics and love. The scene from which the excerpt is taken is when the protagonist is asked by yet another writer friend to write for a certain magazine.

The two people conversing in the back of the room are the protagonist and his writer friend.

Over buckwheat noodles, the friend offers Daisuke an opportunity to write, but Daisuke, who is not strapped for cash, turns him down.This is another important scene in which the character of Daisuke, a man who receives financial support from his parents and lives on unearned income, is contrasted with his friend, who has become a money-grubber. However, as you may have noticed, this scene, too, is not as straightforward as it seems. The man in the foreground is strangely visible.

He just happens to be sitting nearby, but his behavior suggests that he is a Hanashika (Hanahika is a comedian, so to speak, who performs rakugo, a traditional form of comic storytelling that has been around since the Edo period). ) He eavesdrops on their conversation and mimics their gestures, especially those of his writer friend. Rakugo is an art in which a performer plays several characters with only the movements of his or her upper body while sitting down. However, it is strange because it is shown in the front of the screen, leaving the main character out of the picture. While an important conversation is taking place in the background, we, the audience, cannot help but look at the behavior of the performer in the foreground, which makes us smile. This is Morita’s specialty. The question, however, is why this direction is seen as strange in the first place, and why it is perceived as funny.

The first possible reason is that the aforementioned film principle (elimination of superfluous information) has penetrated too deeply not only among filmmakers but also among the general public.

While directors are expected to eliminate as much information as possible when depicting a certain scene, except for that which conveys the message of the scene, the general public rarely has the opportunity to see images other than those that have already been “polished” and therefore perceives any deviation from this as “strange”. For example, if we were to film a scene in which a dog is dying of an illness, who would shoot a TV commercial for an energy drink playing behind the dog’s sobbing owner? Even if it were realistic, information that is not connected to the message being conveyed would appear superfluous, and that is the true nature of the sense of discomfort. And humans are creatures that, when they find something “socially deviant,” try to “correct” it with the tool of “laughter.” (If I were to go into the mechanism of “laughter” from scratch here, it would take too long, so I will write a separate blog about it.) That is why I find myself laughing when I see this staging method, which ignores the theory of “putting Hanashika in front of the two people talking in the back while Hanashika gestures with her hands in the front.

But is that really the only reason?

Is this scene funny only because it is “deviant”? In the case of Morita’s films, I think the answer is no. I think another solution is that this scene is funny because it is probably “Shasei-bun-like” in its depiction.Before explaining this, however, it is necessary to first explain what exactly “Shasei-bun” is.

・What is Shasei-bun?

Shasei-bun is a definition of style in written expression.

At first glance, it may seem strange to bring up the definition of style when discussing the appeal of a film director. First of all, let us look at the general interpretation of the term “Shasei-bun,” which, according to Wikipedia, means something like the following

A text that attempts to write things as they really are through sketching. In the mid-Meiji period (1868-1912), Masaoka Shiki, who was promoting the modernization of haiku and tanka poetry by applying the concept of “sketching” derived from Western painting, advocated applying the same method to prose, which was developed mainly by Shiki and Takahama Kyoshi and played a major role in creating modern Japanese prose.

In other words, “Shasei-bun” is the written equivalent of the word “sketch,” which is used to capture the scenery in front of one’s eyes on canvas in as realistic a state as possible.

Indeed, there are many scenes in Morita’s films that look as if they are real landscapes that happen to be captured by the camera. And it is this very natural way of directing that soothes the hearts of many of his fans.

However, this understanding of “Shasei-bun” alone would lead one to believe that Shasei-bun films are “just realistic images of realistic things. There is still a gap between the Wikipedia definition of “Shasei-bun” and my definition of Morita’s “Shasei-bun-like films. How on earth can this gulf be bridged?

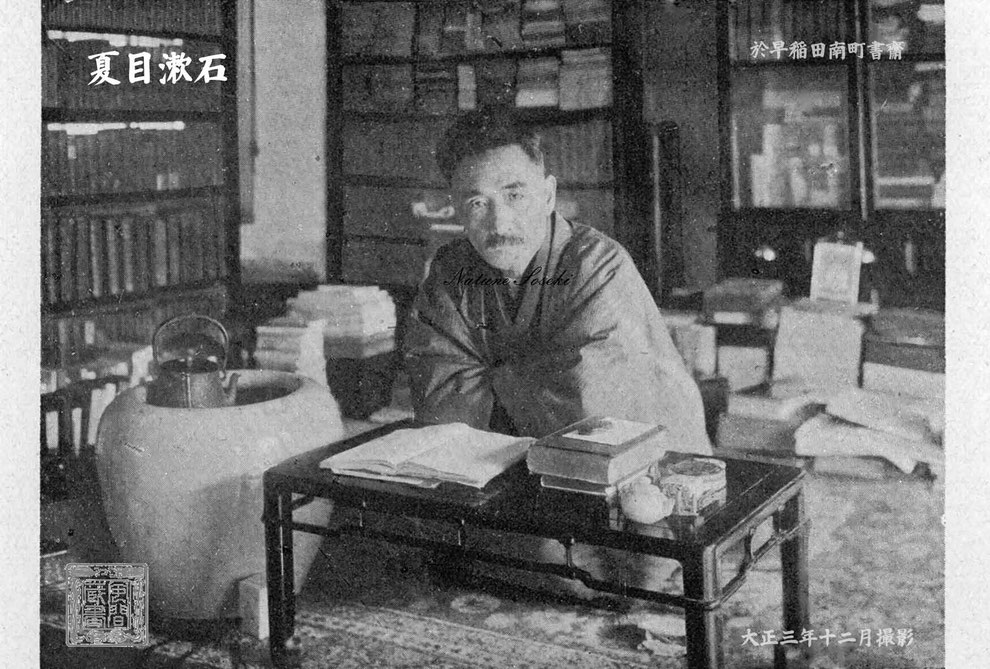

The answer is none other than Soseki Natsume. His innovation in the concept of “Shasei-bun” is the reason why I have described Morita’s films as “Shasei-bun-like.

・Natsume Soseki and Shasei-bun

In the early days of his career, Soseki Natsume discussed Shasei-bun in a critical essay he wrote under the title “Shasei-bun.

This article reveals that Soseki viewed Shasei-bun from a slightly different angle than the above-mentioned theory. The following is an excerpt

Shasei-bun is the attitude of parents toward their children.

Shasei-bun is not a serious thing. No matter how serious the matter may be, it is always done with this attitude, so that when you look at it for a moment, you feel as if you are not going to the bottom. But not only that, because they view the negotiations of worldly affairs with this attitude, they usually include elements of comedy in their writings.

It is true that adults may smile when they see children fighting with each other because they are not in sync with their emotions, but rather they are watching the exchange from a bird’s eye view.

What parent would cry because he or she is emotionally involved with a five-year-old who has had his or her stuffed animal taken away from him or her? Soseki’s masterpiece, “I am a Cat,” as the name implies, features a cat as the main character, and the human drama depicted from the cat’s point of view is somewhat comical, as if he were looking at it from on high.

In this way, Soseki redefined shasei-bun from “mere sketches” to “the fostering of a sense of humor through observation from on high. Morita probably did not miss this renewal. I suspect that he incorporated Soseki’s philosophy into his filmmaking and came up with a style that generates “discomfort” and “laughter” (since he directed the film adaptation of Soseki’s original story, this is not necessarily a wrong guess).

Now, I have gone on for a long time. Based on the above, let me analyze again the scene in Morita’s film.

・Shasei-bun-like Depiction in Morita’s Films

Consider the scene in the aforementioned “Let’s Go on the Express A Train” where the camera simultaneously captures the interaction between Komachi and the female employee, and the fight between the black security guard and the complaining man.

Needless to say, there are two stories going on in this scene. We, the viewers, can see this as a “group drama” as if we were watching from a god’s perspective. What would have happened, for example, if the camera had only focused on the fight between the two men in the background? Perhaps some people sympathized with the loyal gaze of the security guard with his arm outstretched, and cheered in their hearts, “Get rid of that suspicious guy quickly!” Or perhaps some people cried out “Good luck” when they saw the complaining customer who was about to be chased out. In any case, their urgent expressions should immerse us in their emotions and draw us into the screen. However, Morita placed the depiction of this conflict behind the protagonists. Their faces and voices are blocked out, and they become mere scenery the same size as the extras entering and leaving. And because of this, their heated conflict immediately becomes “comic” to us, the audience, who are given a God’s perspective.

But isn’t this what “nature” is? If we look back at every scene in life, isn’t it the same? Some people are serious, while others are not. Some people are crying, while others are laughing. It is real that such opposing situations can coexist for a moment. Despite this, for example, taking out an item such as a camera, intentionally focusing on a desired location, and leading the audience to the desired emotion, is far more unnatural from Morita’s, and by extension Soseki’s, point of view. The above-mentioned mixed space is natural, and when we look at this nature from a high vantage point, we find it amusing and comical. Just like the feeling of a school sports day seen through the laundry from the balcony of a housing complex. This is the true nature of the mechanism behind the “discomfort” and “laughter” in Morita’s films.

Conclusion…

Once again, I have brought up my beloved Natsume Soseki. The public image of him is that he was a nervous, clever, and difficult person. Perhaps this is not entirely off the mark, but on the other hand, I think that Soseki could not help but love the people who are active in this secular world, the sentient beings covered in worldly desires. He was a cranky man who would take out his anger on his wife or his disciples when he was in a bad mood, and who was also very paranoid and worried that people around him were talking bad about him. On the other hand, he was such a philanthropist that he wrote about the lives of ordinary people, including himself, in his novels in detail, from as realistic a perspective as possible, as “lovable and comical.”

I think that it is precisely because of this that he avoided portraying his lovable and comical characters, at least in his own works, as if they were pieces in a game of chess, fitting them into a set plot. As proof of this, he also left the following words in “Shasei-bun”:

What is a plot? The world is unplotted. There’s no point in trying to make a plot out of something that has no plot.

I think Morita probably looked at the world with the same feeling. In his later years, Morita was apparently planning a sequel to ” Let’s go on the express A train.” I wonder if the plot would have been about Komachi and Kodama, this time in a different place, and as usual, a railroad-centered drama. But his dream was not realized, and he passed away. He was 61 years old. It was a regrettable death. He had a lot more to come. It’s likely that Morita, a filmmaker, was just about to reach his maturity, like Hanashika, where the older he gets, the more flavorful he becomes. However, no matter how much such words of regret are spoken, there’s no point. These are words of comfort to myself as a fan of Morita’s films. It may be a little inappropriate to say this, but it could also be said that he finally gained true humor by going to heaven. His world is truly a divine perspective. Only by entering his world can I see the deep blue drama of “lovable, humorous things” that he was looking for in the truest sense of the word. Of course, there, my idol, Soseki-senpai, must already be sitting there, never getting bored, in a special seat for over 100 years. I hope Morita will stand shoulder to shoulder with Souseki, laughing and watching over our plotless story. Such an inappropriate and selfish fantasy just keeps growing.

★Blog writer: Ricky★

Leave all things cultural to me! Ricky, the evangelist of Japanese culture, will turn you into a Japan otaku!

Sources

・Morita Yoshimitsu Wikipedia

・Shasei-bun Wikipedia

・http://books.salterrae.net/amizako/html2/sousekikokkeibungaku.html