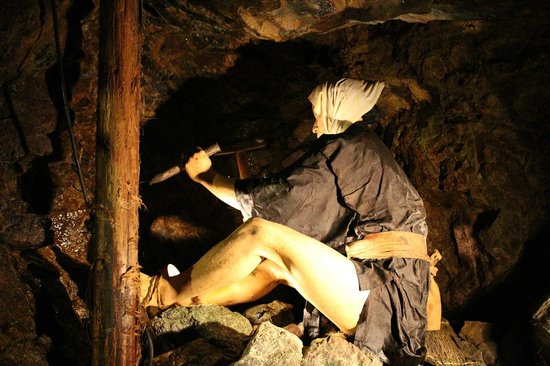

The Ashio Copper Mine is an underground tourist attraction with a 400-year history that once flourished as “Japan’s No. 1 mining town. After the mine closed, part of the mine was opened to the public, and visitors could take a trolley train through the dimly lit, 460-meter-long tunnel. Once down, it was a completely different world from the one above ground. The piercing cold air, the crane beak swinging down, the mechanically realistic wax figures, the 1,234 kilometer-long, unnervingly long, dark tunnel…. It is a vivid memory that I recall well even today. I remember the difference between myself, living a comfortable life working remotely in modern society, and a miner who struggles with lung disease in the darkness of a copper mine, making his living by mining. I think back to the vastly different lives of these two groups of people, and at the same time, I imagine the psychological state of people under such conditions at that time, and I am almost moved to the point of shivering.

Come to think of it, there was a work that used miners and mines as its subject matter, which could be said to be one of the extreme conditions of human beings. In this work, the writer’s exquisite description of the situation, which could only have been written by someone who knew what was going on at the time, and his exceptional abstract ability, made the natural environment of a “mine” into an emotional metaphor. This highly abstract text served as a bridge between the place and the concept of the mine and modern man. The work is called “The Miner” (see below for more details).

The mine has been handed down through metaphor, historical value, and the aforementioned tourist attractions, but it seems that the modern era has given birth to a new concept of “urban mining.

In this article, I would like to introduce the Ashio Copper Mine in the context of a tourist guide, explain its historical background, take another look at the natural environment of a “mine” from various angles, and finally, unravel the modern concept of an “urban mine” created by the mine.

History of Ashio Copper Mine

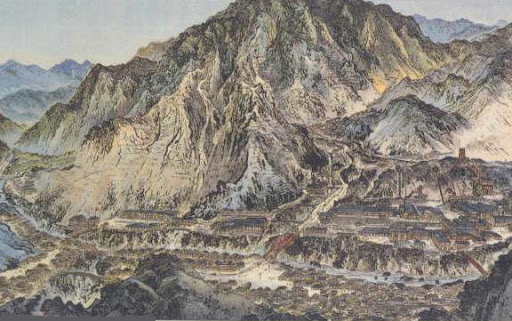

Ashio Copper Mine is said to have been discovered in 1550, and in 1610, two peasants discovered a deposit of copper ore, which led to the start of full-scale mining under the direct control of the Edo shogunate. The shogunate established a coin foundry in Ashio, and the copper mine prospered greatly, leading to the development of the town of Ashio, which is known as “Ashio Senken. The copper mined was used to build Nikko Toshogu Shrine and Zojoji Temple in Edo, and Kan’ei Tsuho, the representative currency of the time, was also minted. During the Edo period, copper production peaked at 1,200 tons per year.

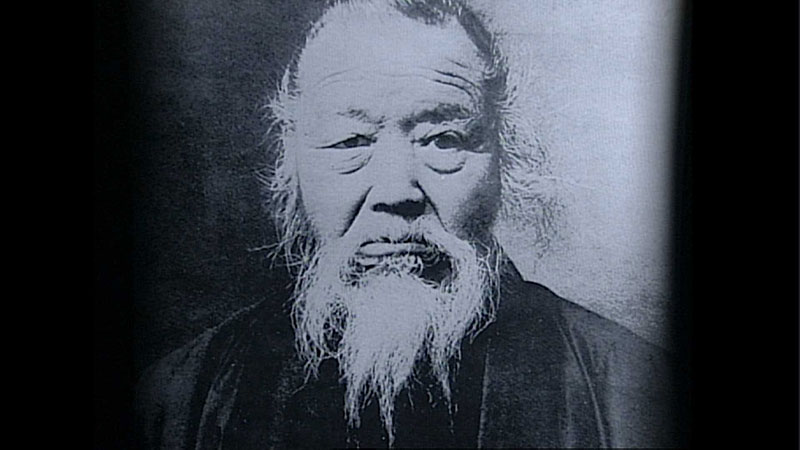

In 1877 (Meiji 10), Ichibei Furukawa began operating the Ashio Copper Mine, and after several years of no success, in 1881 (Meiji 14), he discovered a long-awaited and promising vein of ore. Thereafter, advances in exploration technology led to the discovery of promising mineral veins one after another. After Ichibei Furukawa’s death, Furukawa Mining became a company in March 1905. Against the backdrop of the Meiji government’s policy of national wealth and military power at the time, the copper mine business grew rapidly along with the Kuhara Zaibatsu’s Hitachi Mine and the Sumitomo family’s Besshi Copper Mine, and by the early 20th century had grown into a major copper mine, producing about 40% of Japan’s copper output.

However, behind this development of mining and smelting operations, trees in the Ashio Mountains were cut down for mining and fuel, and the smoke emitted from the factories that smelted the mined ore caused air pollution. The Watarase River, whose source of water was the devastated mountainous area, frequently flooded the area and carried away waste products from the smelting operations, which flowed down the Ashio Mountains and into the plains of the watershed, causing water and soil pollution and widespread environmental pollution (pollution). The so-called Ashio Mine Poisoning Incident became a major political issue in 1891 when Shozo Tanaka made a statement in the Diet.

From the 1890s, although work was done to prevent mining pollution and to repair the Watarase River, the damage caused by mining pollution did not stop, partly because the company prioritized copper production over mining pollution and partly because it was technologically immature.

* Incidentally, the Christian leader Kanzo Uchimura, whom I have already mentioned in another article, is mentioned as a person who fought together with Shozo Tanaka! For more information on his reflections, check out the following!

Perhaps due in part to their efforts, mining operations were suspended in February 1973. The mine closed its history as a copper mine. The tunnels dug by the Edo shogunate and the Furukawa Zaibatsu reached a total length of 1,234 kilometers.

After the closure of the mine, the smelting business continued using imported ore from the company’s hydroelectric power plant and industrial water from mountainsides, but after the discontinuation of freight transportation on the JR Ashio Line in 1989, the smelting business was effectively suspended due to difficulties in transporting ore and sulfuric acid, a by-product of the smelting process, and as of 2008, the smelting facility was no longer used for industrial purposes, As of 2008, the company is only engaged in the recycling of industrial waste (waste acid, waste alkali, etc.) using its smelting facilities.

Apart from these, Ashio Copper Mine Tourism, a facility that tells the history of the copper mine, was opened in 1980 by the town of Ashio (now Nikko City), and has been in operation since 1980. Visitors can enter the tunnels by trolley. Nearby is the Furukawa Ashio History Museum, where visitors can learn about the Ashio Copper Mine, including the mining poisoning incident.

The history of the Ashio Copper Mine is both the history of the copper industry and the history of pollution. This dramatic historical transition has given rise to numerous novels and films. One such work attempts to unravel the Ashio Copper Mine from a completely different angle. This novel was published in 1908, just after the struggles of Shozo Tanaka and others and the Ashio Copper Mine Incident (in which miners destroyed and set fire to mining facilities and other sites to appeal for better treatment), when the issue was still a matter of public concern. This was Natsume Soseki’s “The Miners.

Copper Mine as Metaphor

“The Miner” is a full-length novel by Soseki Natsume, which appeared in the Asahi Shimbun in Tokyo 91 times and in the Asahi Shimbun in Osaka 96 times from the first day of the year 1908 (1908). It is the second work Soseki wrote as a professional writer, following “Agubincho”.

*I have written more about Soseki in another article!

The story of “The Miner” is a little unusual in how it came to be written. One day, a young man named Tomoo Arai suddenly appeared to Soseki and said, “I have a story about myself, and I would like you to write it down in a novel. I would like to go to Shinshu as a reward. Soseki initially recommended that the young man write the novel himself. However, at the same time, he was unable to finish writing Shimazaki Toson’s “Haru” (Spring), which was scheduled to be published in the Asahi Shimbun from the first day of 1908, and Soseki had to fill the gap at short notice. Soseki accepted the young man’s offer, and thus was born a reportage-like work based on the experiences of a real person, which is unique for a Soseki work.

The synopsis is as follows…

After leaving home due to a love affair, the protagonist decides to become a miner, as lured by a broker, and arrives at a copper mine after a strange journey that involves a red blanket and a boy jumping in and out of the mines. He is thrown alone in the kitchen, and while being intimidated and taunted by the odd-looking miners, he descends into the depths of hell. ……Based on the confession of an unknown young man who visited Soseki, this is a unique reportage-like work that consciously eschews a novel-like structure. The story is based on the confession of an unknown young man who visited Soseki.

It seems to be a rare and valuable work, not only because of how it was established, but also because of its style and composition. The following is an excerpt from the beginning of this work.

Once I have run away, there is no way I can return home. I can’t even stay in Tokyo. I have no intention of settling down even in the countryside. If I take a break, they will catch up with me. I can’t stay in the countryside when I have all of yesterday’s troubles running through my head. That is why I just walk.

It is revealed that what is “chasing” him is the “past” of the protagonist, and that the reason he keeps walking is to escape from it. The man “has no clue” about the position of his “present,” which is supposed to be somewhere between the past and the future, and he has no choice but to “just walk”. Mitsuhiro Takeda, a scholar of Soseki, describes the protagonist’s action as “going in the middle”. In this case, the word “going in the middle” is probably synonymous with “going in either direction”. Indeed, the protagonist’s act of pushing toward the darkness, which makes him almost suicidal, may be aptly described as “going in the middle. He is not absorbed in either death or life, but is only vaguely conversing with his inner self.

(Incidentally, Haruki Murakami, who was influenced by this work, has often employed “mine” as a “well” as a place for the protagonist, who is in a state of mental conflict, to confront his inner self.)

The young man tries to deal with the problem as an “inner” problem rather than solving it practically. However, he soon comes to the conclusion that “worrying about one’s shadow in the mirror does not help. If the mirror of the law of the world cannot be easily moved, the best thing to do is to walk away from it yourself.” The young man seems to throw his ‘inside’ back ‘outside’ as if it were an object.

Incidentally, the details of his love affair are not mentioned in the film. However, as one might guess, it was most likely adultery. According to the moral values of the time, a person who committed adultery would have been treated as if he or she were a member of the village. In other words, a love affair was a matter of life or death.

The ladders still has no end in sight. Water drips from the cliff. The cantera is flipped, and it arcs across the face of the cliff, almost disappears, and when it falls to where the hand stops moving, it straightens up again and makes a plume of oil smoke. It flips again. The light moves at an angle. A ladder runs a foot wide, and a gnarled wall is reflected in your eyes. I am horrified. My eyes are dazzled. I meditate and climb up. I can’t see the light, I can’t see the wall. It is just dark. My hands and feet are moving. I see neither moving hands nor moving feet. We live only by touch, touch, touch. To live is to climb. To live is to climb, and to climb is to live. And yet – the ladder is still there.

The ladder in this mine is death the moment you step off. It is too easy to die.

Let’s just die already.

These words repeatedly cross the mind of the protagonist. But even so, his hand never leaves the ladder.

The end of the story comes abruptly. The day after descending deep into the mine, the young man undergoes a medical checkup at the clinic and is diagnosed with bronchitis, making him unable to work as a miner. In the end, after consulting with the head of the Iiba, the young man completes five months of work as a bookkeeper at the Iiba, and then returns to Tokyo.

The film received mixed reviews due to such an abrupt ending and the inconsistent psychological portrayal of the main character. Critics argue that it is impossible for a man who abandoned his hometown to become a miner, and even possibly committed suicide, to have a change of heart so easily. However, I believe that it would be wrong to evaluate this work based on whether the protagonist’s psychology is “realistic or not. As I mentioned earlier, I am convinced that the mine in this work is a metaphor. It is perhaps an abstract representation of the human psychological structure. Earlier, I mentioned that some scholars have described the protagonist’s inability to swing between “life” and “death” as “going in the middle,” and this applies to the mine as well. Blocked from light and unnoticed, he is still moving stealthily toward the darkness. This is just like the act of “going in the middle” itself. The protagonist in the vortex may have been assimilated into the mine. Soseki may have wanted to convey to his readers the contradictions, ambiguities, and contradictions that all human beings have by combining and abstracting the protagonist and the mine. When I saw the mechanical wax dolls moving invisibly in the mountains, I felt that I was able to get a closer look at the reality of miners in those days, and at the same time, I could sense the symbolic elements that Soseki may have picked up from the miners. This may be the reason why the book continues to be read in spite of the fact that it is about a relic of the era, a mine.

Now that I have written about “Mines as Metaphors,” as mentioned earlier, all mines in Japan have now been closed. Nevertheless, we continue to feel, perhaps at the DNA level, the benefits that the mines of those days brought to Japan. A new concept using this term was born in modern Japan. It is “urban mining”.

The Possibility of Urban Mining

An urban mine is a mine of useful resources (e.g., rare metals) that exist in home appliances and other items that are disposed of in large quantities as garbage in cities. It is a part of recycling, in which resources are reclaimed from them and put to effective use. It is also one of the above-ground resources. What are some of the specific examples? Here are some examples.

・Tokyo Olympic Medals

The medals awarded to athletes at the 2021 Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games were made from recycled metals recovered from small home appliances. As part of the “Medals for Everyone Project,” medals to be awarded to athletes at the 2021 Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games were made from recycled metals collected from small home appliances. This was the first attempt in Olympic history to collect approximately 5,000 pieces of metal for gold, silver, and bronze medals as a project with public participation. The target items included a total of 28 items handled under the “Small Home Appliance Recycling Law,” such as cell phones, PCs, and digital cameras. After the Olympics, the “After Medal Project” continues to promote the recycling system for small home appliances.

・Onboard storage batteries for electric vehicles (EVs)

As the world moves toward decarbonization, demand for electric vehicles is increasing and the price of rare metals used in batteries is skyrocketing. Furthermore, various concerns continue to linger, including the impact of the new coronavirus on production, the invasion of Ukraine into Russia, and the uneven distribution of production areas. Against this backdrop, the European Battery Regulation proposal was announced in December 2020 in Europe, bringing renewed attention to urban mines for recycling rare metals. The proposed regulation would require a minimum content of recycled materials for nickel, cobalt, and lithium used in EV storage batteries and other products from January 1, 2030 onward. This trend is likely to grow as countries outside the EU, such as Japan, feel threatened that they will not be able to sell their own batteries and EVs to EU countries.

・Sustainable Jewelry

Some brands are creating sustainable jewelry as a way to make people who do not have a strong interest in the environment aware of the existence of urban mines and recycled metals. NOWA” of the Netherlands has partnered with ‘Closing the Loop,’ which promotes the recycling of discarded smartphones, a problem in Africa, and is working to create a system of circular economy. YURI SATO JEWELRY in Japan is focusing on environmental and human rights issues and the depletion of resources at jewelry mining sites, and is working to give new value to discarded items that would otherwise be discarded. What at first glance appeared to be nothing more than a pile of trash is now being put to effective use in these various applications with the help of modern technology under the name of “mining. Incidentally, in the third case, sub-sustainable jewelry, the author is also practicing.

There is a Swiss brand called FREITAG, which mainly recycles waste materials such as truck covers, and I use a messenger bag from this brand. I use a messenger bag made of this material, which is durable and water-repellent, and I love it. I am also a part of the new cultural system of “urban mines”.

Conclusion

Mines are shedding their negative image as “pollution” thanks to the achievements of Ashio Copper Mine and other great figures. This is due to the literary aspect of the mine as a metaphor by writers such as Soseki, and the new concept of “urban mining” brought about by technology.

When visiting Japan, it is good to visit the top-ranked tourist spots and leisure facilities, but sometimes it is better to go and see historical and cultural assets that are a mixture of positive and negative aspects. You will get a glimpse of the negative aspects of history that you cannot experience at popular tourist attractions. At the same time, however, it is also a shadow of the efforts of our predecessors. Success is impossible without failure. The Ashio Copper Mine is a history of industry, a history of technology, and a history of the scrap-and-build of mankind.

★The writer of this blog: Ricky★

Leave it to us when it comes to cultural matters! Ricky, a Japanese culture evangelist, will turn you into a Japan geek!

Source

Ashio Copper Mine Official Website

Ashio Copper Mine Wikipedia

The story of “The Miner” [Soseki Natsume] fufufufujitani note

The Runaway in Soseki Natsume’s “The Miner

IDEAS FOR GOOD

A magazine of ideas from around the world to improve society.

Urban mine Wikipedia