Taketori Monogatari (The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter), the oldest Japanese tale established in the early Heian Period, and After Yang, a science fiction film produced in the United States in 2021.

To the best of my knowledge, no one has ever connected these two works that are so far apart in their ancient and modern worlds. When I saw “After Yang” at the theater a few years ago, I was not only impressed by the wonderful content, but also recognized traces of “Taketori Monogatari” that had passed over 1,200 years. This was a thrilling discovery, and it made me wonder why on earth the producers of this film chose to incorporate elements of classical Japanese literature into a modern science fiction film, and what the significance of such a decision was.

In this blog, I will begin with a brief introduction of the two films and then analyze their messages and their relevance to each other in my own way.

What is “Taketori Monogatari”?

・Outline

The story is said to be one of the oldest stories in Japan, dating from the late 9th to early 10th century, and is one of the earliest stories. In modern times, it has been accepted in various forms such as picture books, animations, and movies under the title of “Kaguyahime. The author is unknown. The estimated literacy rate of the time makes it difficult to imagine that the author was a commoner, and since the author belonged to the upper class, lived near Heian-kyo where information on the nobility was available, and the story has anti-establishment elements, it is thought that he was not a member of the Fujiwara clan that held power at the time.

The story is full of mysteries, but here is the synopsis…

One day, an old man who picks bamboo for a living finds Kaguyahime sleeping in a bamboo grove. He brings her home and raises her with his wife as if she were his own child. Kaguyahime grows up to be as beautiful as a nymph, and her beauty spreads through the village and eventually spreads to the political world. Five noblemen, one after the other, ask for her hand in marriage, but Kaguyahime fails to meet their unreasonable demands as a condition of marriage. In the end, even the emperor asked for Kaguyahime, but she did not agree to his request. She then tells her foster parents,

“When the moon is full, I must return to heaven.”

The emperor and the elderly couple prepare for war to resist the moon, but they are too divine and luminous to be driven back by human power. At last, Princess Kaguyahime was clothed in feathers by the heavenly beings and forgot everything that had happened on earth. Then, on the fifteenth night of August, she left for the world of the moon.

It is a beautiful and sad story. In this comparative study with “After Jan,” I would like to focus on the metaphor and message of the existence of Kaguyahime in the story of “Taketori Monogatari.

・Kaguyahime Metaphor

In the first place, Kaguyahime is a celestial being, that is, a being who has neither “reason” nor “troubles” on earth. She was dropped to earth as a baby because she had committed a sin in the heavenly world (the details of which have not been revealed). She also possesses a beauty that is far removed from the world, and when she reaches the age of womanhood, she is beset by a storm of courtship from powerful men of renown. However, she has no concept of the power of the time or the institution of marriage, so she rejects them, saying, “Why should I do such a thing? (The character of “the most beautiful woman in the world” is also used in the film to contrast with the men who flock to her and their troublesome lives.)

) However, among the numerous suitors, Kaguyahime had a kind of love for the emperor, who was sincere and devoted to her. Perhaps she had become slightly “humanized” because of her upbringing by humans. As evidence of this, she left behind some lines that suggest her lingering feelings for the emperor and for the earthly world. In the last scene, Kaguyahime writes a letter to the emperor, “Before that,” she says, “I will put on a robe of feathers for you.

The one who wears the heavenly robe of feathers has a different heart from the others.

He sent many people like this to keep me here, but the One who would not allow me to stay came and took me away, which is unfortunate and sad.

And true to her word, Princess Kaguyahime, in her robe of feathers, ascends to heaven without looking back, her memory of all her time on earth vanished.

How do you read this scene?

I think that this story is, in essence, a work about love for human “troubles. Human beings are weak, and therefore tend to depend on systems created by their afflictions, such as power, institutions, love, and so on. However, it is precisely in these areas that the imperfection of human beings, and therefore their loveliness, is found. Kaguyahime, although humanized, was originally a celestial being. That is why she was able to look at the aforementioned troubles from a flat perspective and understand their ambiguity, foolishness, and beauty.

・summary

In other words, “Taketori Monogatari” is an ethereal and grandiose fantasy, but at the same time, it is a socially conscious work that is also a criticism of power and institutions.

Now, after this lengthy commentary, what kind of influence has “Taketori Monogatari” had on contemporary American cinema?

Now, let us introduce the curious “AfterYang.”

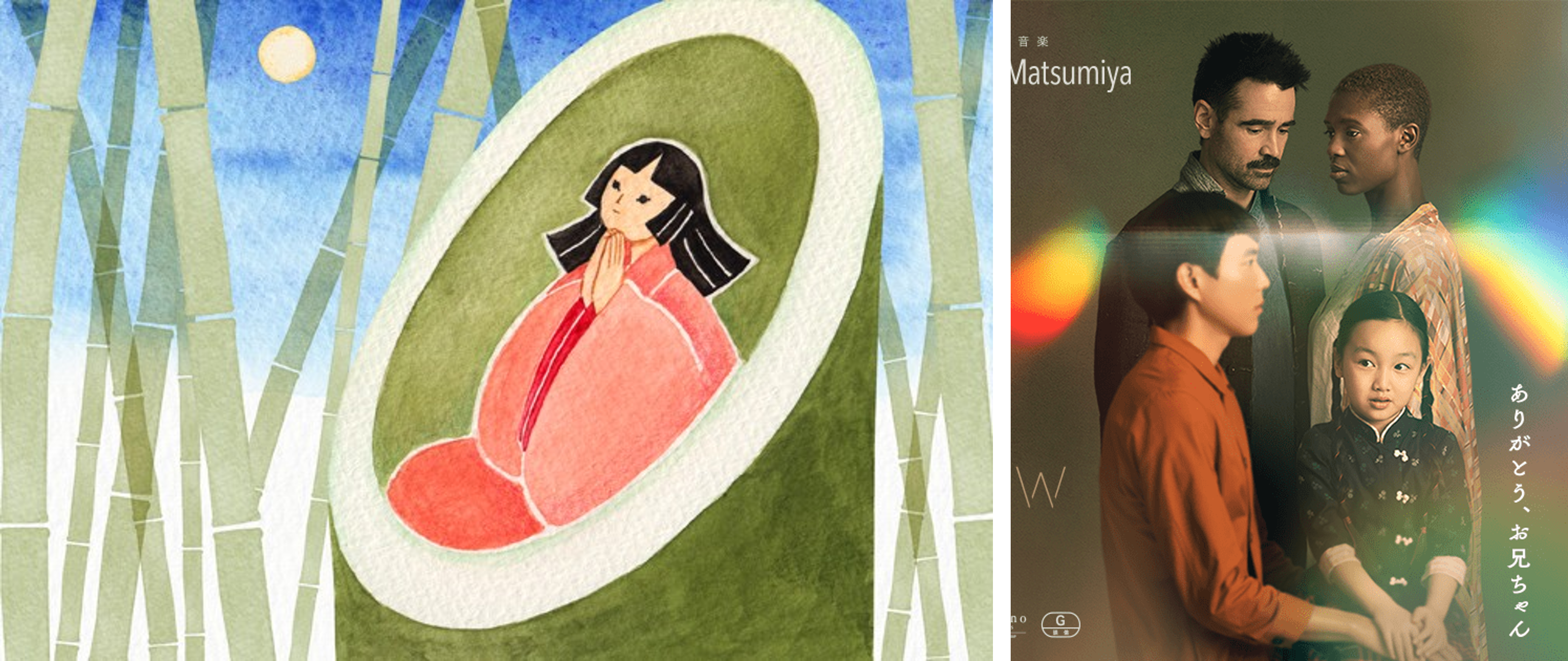

What is “After Yang”?

・introduction

The film is based on the 2016 short story “Saying Goodbye to Yang” by Alexander Weinstein. It stars Colin Farrell and is an internationally acclaimed classic that won the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actor and premiered at the 74th Cannes Film Festival. The synopsis is as follows.

In the near future, humanoid robots known as “techno” robots have become widespread. Jake, his wife Kayla, and their adopted daughter Mika, who is of Chinese descent, run a tea store. While searching for a way to fix it, Jake discovers a “memory device” in Yang’s body that records a few seconds of video every day. It shows Jan’s kind eyes looking at his family and a young woman, Ada, whose identity is unknown. What does Jan’s memory tell him?

Although the film is set in the near future, the scenery captured by the camera has an Asian flavor, perhaps due to the fact that the director, Kogonada, is a Korean-American Asian, and the composition gives a nostalgic impression to us Japanese. The tone of the film is also tranquil, with no over-the-top direction or background music. The main character is a tea shop owner who deals only in tea leaves, and at first glance, one might think that the film depicts an era a decade ago.

However, once the scene changes, the film is littered with futuristic elements such as automatic cars, the globalized family structure of Jake, a white man, Kayla, a black woman, and Mika, an Asian woman, and a dance battle with remote participation.

・theme

The film’s subject matter centers on Jake, who looks into Jan’s broken memory device and shakes up philosophical propositions such as “what is death,” “what is family,” and “what is country.” One of the most interesting settings is that of Jan, a machine “a babysitting AI robot named Techno that transmits cultural roots to war orphans.” Jake and Kayla have the Chinese techno Yang live in the house so that Micah does not feel alone, or so that he can learn about his Chinese national roots. And Yang, in order to fulfill his role, also teaches Micah about the diverse knowledge of Asian culture and history. Meanwhile, Mika, an orphaned, adopted daughter, is asked by a schoolmate, “Where are your real parents?” She feels rootless and insecure. Will it really be an AI robot, blood, looks, or language that will cure Mika’s loneliness?

As if in response to this question, one day Jan takes Mika out to a farm. One day, Jan takes Mica out to the farm, where she sees a “grafting” plant, in which different plants are connected to grow as one plant, and Jan says to Mica, “Look at this.

Jan looks at it and says to Mica: “Look at this. Look what’s happening. Look, these branches are coming from different trees. But now it’s the same tree.

What does this statement mean? The answer can be gleaned from Jake’s access to his memory. Jan had once fallen in love with a cloned woman named Ada.

・Why people are people

What are the elements that make us human? Is it blood, appearance, or language? We tend to think that these factors make us human (the Nazis considered Jewish “blood” inferior and not human). In this sense, a clone is a copy of someone else, a fake in terms of blood, appearance, language, and so on. Therefore, the main character Jake, for example, is disgusted by Ada (because she has fake “blood”). Jan, the robot, however, has no such prejudice and is able to love her “as she is. Furthermore, Jan knew the girl who was the source of Ada’s copy. Ada’s original copy was born, died, and then met Ada, who looked exactly like her. And then she encounters the lives and deaths of various people. Through these experiences, which are unique to home robots, Jan came to the conclusion that “in the end, we are all the same. Regardless of blood, country, appearance, or language, human beings cannot transcend this great tide of birth and death. They all start from the starting point of “life,” and must merge at the ending point of “death,” and their essence remains the same. The concept of “country” is nothing more than a system created linguistically by people. That is why Jan was able to put the line, “It is the same tree now,” to Mika.

・Summary / Interview with the Director

In the end, until the last minute, Jan’s breakdown is not fixed and he remains in sleep mode. Was it his final role to give the word “graft?” The director, Korean-American Kogonada, said in an interview.

“One of the things we wanted to explore was that the robot is Asian, and the artist is not Asian. But even that notion of Asian is manufactured, like the robot.

I am Asian. When people look at me, they have a lot of assumptions and expectations, and I have to fight against them. I have always struggled with what it means to be Asian. I think it is an ongoing struggle for people who feel uncomfortable being Asian. So this work was a way for me to sort out my longing for a place where I belong.”

Relevance of the two works

・Yang = Princess Kaguyahime? Impact on those left behind

Incidentally, although it is not well known, “Taketori Monogatari” has an epilogue describing the people left behind after Kaguyahime’s departure. The contents are as follows.

Kaguyahime returns to the moon. Taketori no Ou and the elderly woman shed tears of blood and worry, but there is nothing they can do. The old man, who has lost his reason for living, does not take the medicine of immortality and falls ill in bed. Meanwhile, the emperor hears the details of the situation from the head lieutenant and receives a letter from Kaguyahime and the Elixir of Immortality. The emperor was deeply moved when he read the letter. The emperor summoned his ministers and lords to inquire about a mountain near the heavens. When the emperor learned of the existence of a mountain in Suruga, he ordered an imperial envoy named Tsuki no Iwasasa to go to the top of the mountain and burn the letter and the elixir of immortality presented by Kaguyahime. He named the mountain Mount Fuji. Fuji, from which smoke still rises incessantly.

Why did the emperor not take the Elixir of Immortality? Perhaps it is because the emperor, who inherited Kaguyahime’s legacy, understood the love for “vexations. All vexations, after all, originate from death. In other words, if there is no death, there are no vexations. It is precisely because of the limitation of death that we struggle and suffer in order to fulfill our limited “life. Being tormented by such “troubles” is nothing more than the determination to live this short life with care. Perhaps it was only by interacting with Kaguyahime, who was given “eternal life,” that the emperor was able to gain a flat perspective on his “limited life” and learn to love it.

What about the case of “After Yang”? If we dig deeper into the theme of “the person left behind,” if the “person left behind” in “Taketori Monogatari” is the emperor, the corresponding person in “After Yang” is probably the adopted daughter, Mika.

As mentioned earlier, Mika has had a hard time recognizing anything positive in her “orphan Chinese” roots. Then, by summoning a certain celestial being named Yang, she was freed from the limitations of the system of blood, appearance, country, and riddle. Finally, the film succeeded in taking a positive view of the cultural roots of China from a flat perspective. As proof of this, the last words he muttered to his unmoving Yang partner were in Chinese. Neither Jake nor Kayla, who is a parent, understands Chinese. And to our surprise, this scene was not even subtitled, so we, the audience, could not understand it either.

(Incidentally, I later looked it up on the Internet and found that the Chinese for the scene was, “Thank you for being the best big brother in the world.” I miss you.”)

More than 1,200 years after “Taketori Monogatari,” the concept of nation has changed, and new conflicts brought about by globalization are upon us. More and more children like Micah will have existential angst. This is why I believe that the producers of “After Yang” prepared Yang, a celestial being, to overcome this newly emerging existential anxiety.

In other words, in both “Taketori Monogatari” and “After Yang,” the filmmakers’ intention was first to introduce a [non-human] character, a celestial being or robot, and thereby introduce a flat perspective. Then, by bringing to light the structure of anxiety caused by the “troubles” (the system), the filmmakers may have intended to make the viewers love the “troubles” (the system).

・Bamboo” in the background”

Toward the end of “After Yang,” there is a scene in which we see a glimpse of the inside of the museum, where Yang’s donation is being sought. There, to my surprise, are a number of objects resembling bamboo. And they are glowing!

When I discovered this, I jumped up and down.

Conclusion

We have analyzed the story of the celestial beings in “Taketori Monogatari” and the AI robots in “After Yang,” two works from different eras and with different themes, but with the same underlying philosophy. Don’t think that they are just figments of the imagination. These works, especially those that are science fiction in nature, contain a great deal of metaphor and raise fundamental philosophical questions such as “what is human” and “what is life? And this, I believe, is the beauty of fantasy stories. For example, if someone were to suddenly ask us with a difficult face, “What is death? That is why people today continue to mix science fiction, fantasy, mythology, and all kinds of entertainment elements to create fantasy stories, taking advantage of the rambling nature of humankind that is built into us at the DNA level. We trust that someone will decipher the great metaphor. I would like to continue to experience works from every possible era, country, and language. Perhaps the gods of entertainment will bring us another wonderful encounter like “Taketori Monogatari” or “After Yang”.

【Ricky】