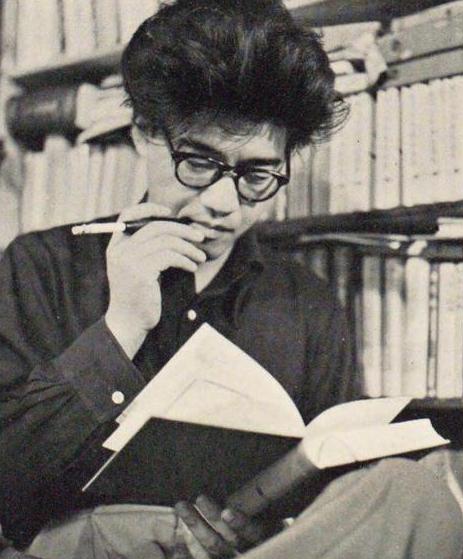

There is a Japanese film that is getting a lot of attention right now. The title is “Box Man. As the title suggests, it is about a man who lives in a cardboard box. This does not mean that they settle down and live in a specific place like a house, like homeless people do. Instead, the box men in this story first hollow out the bottom of their own cardboard boxes and cover themselves with them. Then, they live in a mobile home-like environment, sometimes staying there and sometimes moving on foot as needed. I am sure that the reader now has a very strange visual in his or her mind. By the way, this movie is based on a rather old novel. The novel was written by Kobo Abe in 1973, and its outlandish setting and worldview greatly satisfied the world of literature fans, making it a smash hit.

For more information on Kobo Abe, please read the following blog!

https://t-yaoyoroz.com/tokyo/en/2023/11/30/osorezan-japans-three-most-spiritual-mountains-where-you-can-see-a-seance-by-an-itako- closest-place-to-the-dead/

Of course, as a fan of Kobo Abe, I read this work when I was a student, and I remember struggling with its difficult writing and word play rich in metaphors. I remember that I had a hard time with the difficult text and the metaphoric play on words. It is now being released in theaters to rave reviews. How on earth was this absurd world expressed not in a novel but on film? Also, is there any significance in the fact that it has been transformed into a movie instead of a novel? On the occasion of the film’s release, I would like to analyze the film in my own way.

What is “The Box Man”?

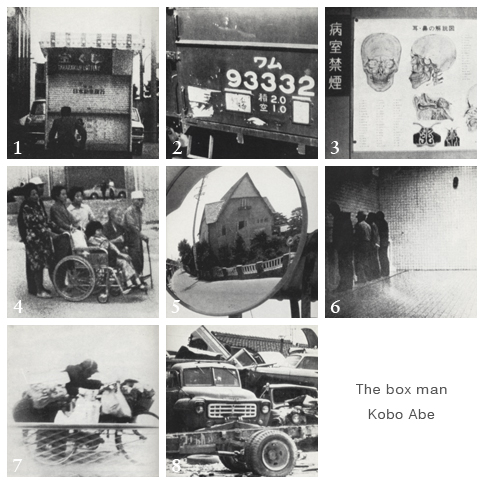

Hakko-Otoko” (Box Man) is a full-length novel written by Kobo Abe. It is the story of a “Hako-Otoko,” a man who wanders around the city wearing a cardboard box from head to waist, staring at the outside world through a peephole. The experimental composition consists of various time-space chapters, such as a memoir written by the “Box Man,” sentences apparently written by other people, suddenly inserted allegories, newspaper articles, poems, a frame of negative film at the beginning of the film, and eight photographs. It is a development of the anti-novel (anti-novel) that attempts to question the very act of human writing, and at the same time, to dissimulate the conventional narrative world and structure of the novel, while at the same time pursuing anonymity and proof of absence in the city, recognition of the self/other relationship of seeing and being seen, and human “belonging. The synopsis is as follows.

A “box man” chooses to live in the city wearing a cardboard box, disconnected from society and not belonging anywhere. One day, “I,” a box man, is approached by a nurse who wants to buy a box. Resisting the idea of destroying the box, he goes to the hospital where she works to refuse the request, only to discover that there is a doctor who has become a counterfeit Box Man. The progression of the strange relationship between “Boku,” the bogus box man, and the nurse is interspersed with episodes of other box men and boys, inviting mystery and surprise to the reader.

It seems to be as difficult to understand as “Kangaroo Notebook,” which I have already introduced to you. When I first read it, I had a hard time understanding its nested structure, and I did not know where to begin to unravel it. Of course, this work was a sensation in the literary world at the time of its publication, and it was a historical masterpiece that caused a great deal of headaches for famous critics. But even so, it was written in 1973. The world has changed drastically in terms of economics, politics, and technology. People’s values must have been updated accordingly. For such people of today, is the story of a man who seeks for existence and hides himself in a cardboard box really applicable? Do not underestimate its value. The value of this work lies in its universality that transcends the changes of the times. No matter how much the external environment changes, “The Box Man” will always stand tall at the center of the literary world without fading away. Even a single item, such as the cardboard box, has been reinterpreted with a high degree of abstraction from Abe’s unique perspective and sublimated as a metaphor. When read by a modern reader, the metaphor of the “cardboard box” seems to suggest the arrival of the Internet and social networking services. Now, let me try to interpret this monumental masterpiece of Japanese literature, which can also be called a book of modern prophecy, from my own point of view.

『箱男』を現代人として解釈する

Once in an anonymous city, for anonymous citizens only, where doors are open for everyone without any barriers, where strangers don’t need to be afraid of each other, where you can walk on your head or fall asleep on the side of the road without any repercussions, where you can stop people without any special permission, where you can sing your song without permission, where you can mingle with the anonymous crowds whenever you want to, where you can be a stranger, where you can be a stranger without any repercussions. If you have ever envisioned or dreamed, even just once, of a town where you don’t need special permission to call people over, where you are free to sing your song of choice, and where you can mingle with the anonymous crowds whenever you like, once you’re done singing, you are free to do so. If you’ve ever imagined or dreamed of such a city, you’re no stranger to it.”

This is an excerpt from “Box Man,” but when I read it at the time, I remember intuitively thinking, “That’s what Twitter is all about. Twitter is open to everyone, and anyone can leave at any time. And the “anonymous account” on Twitter corresponds to the “box” in “Box Man. When you wear the box, you become invincible, and you can say all the things you would normally not be able to say. When the Internet first emerged, the world was described as an oasis for nameless citizens, and 2channel (the name of a website that includes many electronic bulletin boards) is a typical example of this. For those who are depressed in the real world, the anonymous electronic world must have felt like a way to free themselves from the fences of everyday life. However, it has been 30 years since the Internet became popular. What do you think of the current state of the Internet? The paradise of those days has now become a hell. Slander, abuse, apologies, account deletions, lawsuits… There is no end to the daily verbal altercations and troubles on social networking sites, especially Twitter. How did this happen? I suspect that the answer can be found in the relationship between the anonymous perpetrator and the box man. While diving into the sea of anonymity is weightless and comfortable, there are risks involved. I would like to introduce a recent comment by philosopher Ippei Taniguchi on Twitter regarding the use of real names and anonymity.

[I don’t know, when you’re anonymous, it feels like you’re being forced to “speak your mind,” and you feel pressured to “see, no worries, come on, you can show us who you really are.”

[And of course, no matter how you act, they say, “Heh! That’s the real you!” So the psychological burden of doing something anonymously is so high that I’m at a loss as to what to do.”]

Another user,

“If it is discovered that the person is saying something in an anonymous form in addition to his/her real name, it will inevitably be assumed that the anonymous form is speaking his/her “real mind”…”

Taniguchi also commented on this.

└ [Yes. And that “structure” itself is intolerable to me. That is, to have something like “true feelings” assumed against me somewhere, even if they are not revealed!

[When I talk about something anonymously, I get intensely anxious, thinking that maybe there is something like “true feelings” in me, and that this is exactly what I am talking about now. I feel intensely anxious. It is almost like fear.

Well, it is very easy to understand. Becoming a “box man” may at first glance appear to be an escape from reality, but in fact, as Taniguchi says, it may be an act of taking on a whole new psychological load. The reason why Hakonin seem so painful in this work is not because of their shabby appearance or lifestyle, nor because they are labeled as dropouts, but because they are so sad in their blind faith in the illusion of “true heart” or “existence” or whatever you want to call it. What makes us feel pain and disgust at the same time is not only a sense of resistance to being “peeped at” but also a sense of resistance to being forced to accept the illusion of “true heart. The presence of the box man makes us feel as if our “true feelings” are real, and unconsciously gives birth to the perception that “they may be living in the world of truth…,” which may manifest itself as a sense of aversion. But of course, there is no way to prove whether “true feelings” are real or not. The “true feelings” or “existence” that Hakono-o evokes is nothing but an illusion. As proof of this, the author Abe himself left the following words.

The city reeks of heresy. People seek opportunities for free participation and dream of eternal proof of absence. Then, some people slip into a cardboard box. As soon as they put on the box, they become no one. But to be no one is to be anyone at the same time. You have the proof of absence, but you have given up the proof of existence instead. It is an anonymous dream. How much can one endure such a dream?

Yes, being a box man is both a dream and a normalization of pain. Instead of being freed from the ties of a “name,” being able to access all spaces, act, and even speak, one is required to give up the proof of existence. This is why the end of the box men is so tragic. They have been forced, albeit by their own accord, to live out their illusions of “true feelings” and “existence,” and they have gone mad. It is interesting to note that Taniguchi’s point was made in the world of Twitter, where anonymous “box men” are rampant. It seems to me that anonymous accounts = a discourse that has tapped into the black box that these box men most did not want to be dug up. In other words, the anonymous accounts on Twitter are a scream of slander and invective, the end result of the box men who could not endure their dreams.

Movie “Box Man” / Original Story + Additions in Alpha

The following is an excerpt of the introduction from the official website.

Twenty-seven years after the tragedy, we are finally witnessing a miracle of persistence. Gakuryu Ishii takes on the trap set by world-famous author Kobo Abe! Hakon Otoko” is a masterpiece published in 1973 by Kimibo Abe, a writer whose works have been translated into more than 20 countries and have an enthusiastic readership all over the world. Since its publication, several prominent European and Hollywood film directors have attempted to adapt the story into a movie, but the projects were repeatedly launched and then abandoned. Finally, in 1986, Kobo Abe himself directly asked Gakuryu Ishii (then Sogo Ishii), who had made his shocking debut with “Crazy Thunder Road” and had always been at the forefront of Japanese indie cinema, to make a film adaptation. Finally, in 1997, the production was officially decided, and the staff and cast went to Hamburg, Germany, where the film was to be shot, but the day before crank-in, the shooting was abruptly halted and the project became a mirage…. However, Director Ishii did not give up. Twenty-seven years after the tragedy, in 2024, which coincidentally is the 100th anniversary of the birth of Kobo Abe, he finally completed “Hakon Otoko”. The film stars Masatoshi Nagase, as he did 27 years ago, along with Koichi Sato, who was also scheduled to appear in the film, as well as Tadanobu Asano, who is active on the international stage, and Nana Shiromoto, who was selected from hundreds of people who auditioned for the role. The film premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival this year and was called “the craziest film of the year” by the festival director!

I watched it the other day and found it to be a masterpiece. Below I would like to discuss some of the points of the movie and the differences from the original work.

・Jazz

When reality and fiction intersect, the jazz music echoing in the background was impressive. The bewitching saxophone sound, which seemed to be spun by improvisation, seemed to have the effect of transforming the reality surrounding the main character into something different. The melody, which was not a violent strumming, but rather a spacey, shimmering melody somewhat akin to slumber, made it ambiguous whether the world unfolding in front of one’s eyes was really reality or a dream. This kind of direction is unique to the expressive technique of “film,” which is a comprehensive art of visuals and music. I felt that the transcendental back-and-forth between the world seen through the box and reality, or the separation or confusion between the two, in “The Box Man” was well expressed, transcending the limitations of written expression. Incidentally, this is a digression, but when I saw the film, I was reminded of David Lynch in his use of jazz music to create a different reality. And as I suspected, the director, Mr. Ishii, seems to have been greatly influenced by Lynch. In an interview with a magazine, he made the following comment about David Lynch’s musical expression. I feel a kind of hypnotic effect of rhythm, like the waxing and waning of the moon, like the waves that come and go, that take you deep inside and then bring you back out again. It’s like a repetition of pleasant music and unpleasant music. I think it is quite calculated. I think you are studying mysticism or esotericism. I think he has mastered the specific technique of moving lightly between reality and the other world. Lynch’s crossing between reality and the other world must have been a major influence in expressing Hakon Otoko’s interplay between “this world” and “that world.

・The Presence of Surveillance Cameras

At the beginning of the film, there was a scene in which surveillance cameras installed all over the place were capturing the box man. The doctor, who is a character in the film, monitors the images from the surveillance cameras, which were not in the original film. We, the audience, are forced to stare at the man in the box through the monitor together with the doctor. At this point, the man in the box turns to the “seen” side. In the novel version, the story proceeds from the viewpoint of the man-in-the-box. In other words, in the novel version, Hakonin is basically the “viewer,” and it is the reader’s role to be close to his perception of the world and his way of perceiving existence. Rather, the audience in this film has the ambivalent position of being the same as an unspecified number of people in the city who are “seen” by the box man, while at the same time “seeing” him through the surveillance cameras (come to think of it, the cinema is like a cardboard box, with 16: (Come to think of it, the cinema is like a cardboard box, and the 16:9 screen is like a peephole.) In other words, this surveillance camera staging suggests that “in our time, everyone has an anonymous gaze”: Instagram, Facebook, TikTok…. We live in an age where anyone can become an anonymous observer, peering into the daily lives of their subjects. And that gaze, in this story, and by extension, in this modern age in which we live, does not remain one-sided…

・The meaning of the line “The box man is you.”

At the end of the film, there is a scene in which the main character throws out to the audience, in a low, strong voice, “The box man is you,” in the narration. Such a line does not appear in the original film. What on earth was Ishii’s intention in adding this line? To find out, we need to think about communication in the modern age. With the development of technology, pseudo-communication has become widespread in this world. This started with one-way communication like surveillance cameras that only “see” the subject, and has expanded to mutual communication like social networking services. Coupled with the recent increase in awareness of risk management (e.g., countermeasures against suspicious persons), the need for direct communication has been fading away. In the common areas of condominiums, there are now signs that say, “Please do not greet each other, even if you are residents of the same building, as it may frighten children. Direct communication is being replaced by pseudo-communication through the power of technology. However, what is happening as a result of this is that

However, this has caused the aforementioned problem of “dependence on one’s true feelings (existence). Pseudo-communication through technology has given people the voice of a nameless person. In other words, anonymous accounts on Twitter. They mistakenly believe that they have the right to say whatever they want using anonymity as a shield. Unsurprisingly, what they say is sometimes seen by thousands or tens of thousands of people. And without realizing it, the sender or the people who see their statements are caught in a quagmire of illusion about their true feelings and existence. Neighborhood well-wishers’ meetings are replaced by Internet bulletin boards, and words that were once exchanged in good humor are transformed into language that one would be afraid to even utter. Like an Internet lynching, a person with no name is publicly exposed by a person with no name, and is beaten to a pulp. All of this proceeds without the intervention of real names, and all of it remains anonymous. This is a modern disease brought about by technology. In the original story, the focus was on the “dependence on the true heart (existence)” of a few specific people. However, Ishii probably felt the need to suggest that the state of modern Japan is a “nation-wide box man state,” if you will, in order to translate the story to the present day. We live in an age where everyone has a smartphone, access to the Internet, and the ability to speak anonymously. Today, everyone can be a box man without even wearing a cardboard box. And even today, they are pursuing the illusion of their true feelings, getting hurt, and getting hurt. I couldn’t help but hear that low-pitched, angry “You are the box man,” as if it were a warning to such modern people.

★The writer of this blog: Ricky★

Leave it to us when it comes to cultural matters! Ricky, the Japanese culture evangelist, will turn you into a Japan geek!

Source

・Box man Wikipedia

・Hakon Otoko Movie Official HP