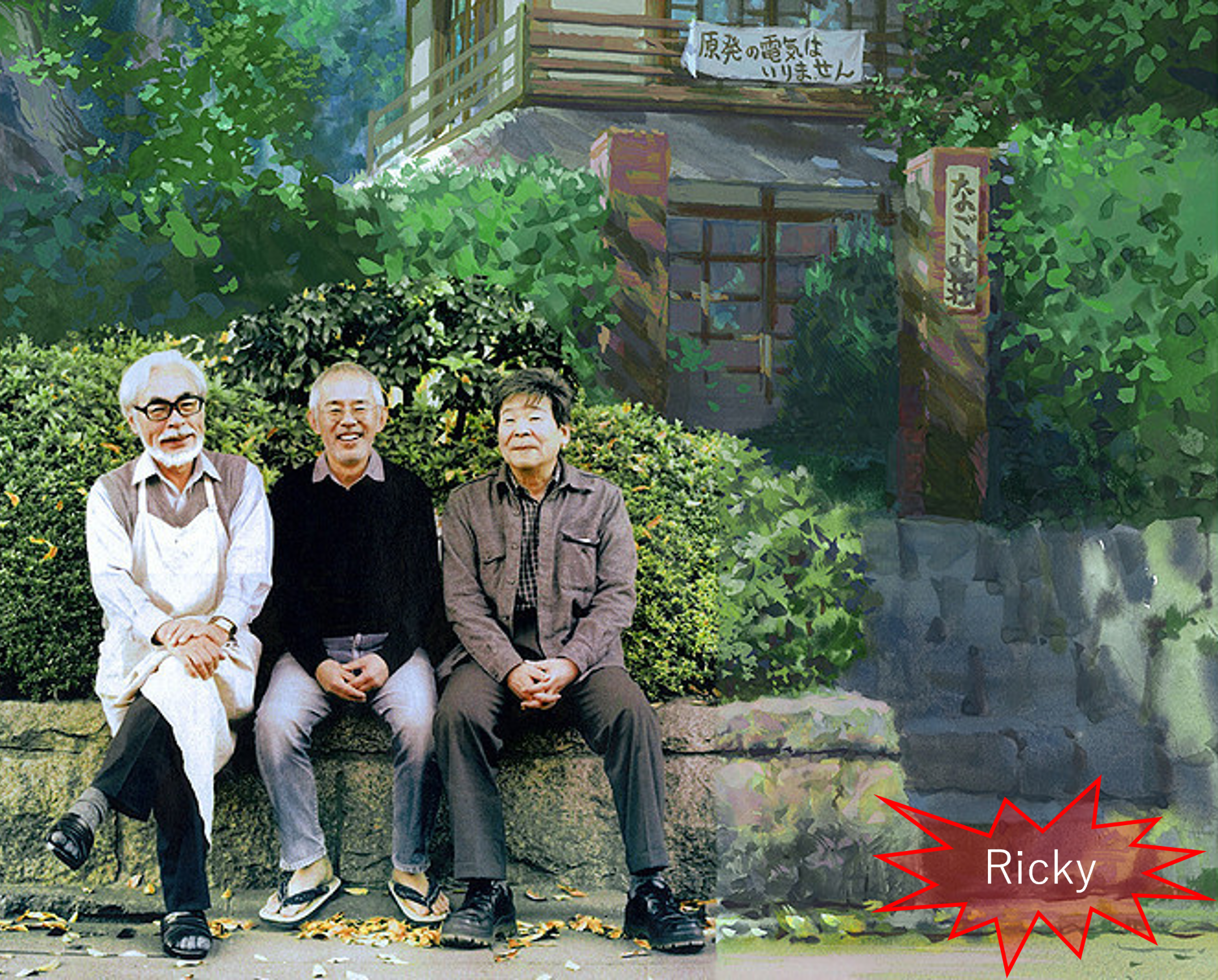

Isao Takahata is the twin of Hayao Miyazaki as the director of Ghibli. Although his sales are not as high as those of Hayao Miyazaki, it is no exaggeration to say that the eccentricity and novelty of his cinematic expressions will remain in the history of Japanese cinema. In my opinion, what is particularly noteworthy about his directorial approach is his “music. In this article, I would like to focus on the film music of Isao Takahata, a rare director.

About Isao Takahata

Isao Takahata (October 29, 1935 – April 5, 2018) was a Japanese animation director and film director. He was the president of the Hata Office and a director of the Tokuma Memorial Animation Culture Foundation. He was a lecturer at Nihon University College of Art, a senior researcher at Gakushuin University Graduate School of Humanities, and a visiting professor at Tama Art University. He is also a film producer and translator of French literature (Jacques Prévert). After directing his first feature film, “The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun,” he moved to A Productions in 1971. After working on such animated TV series as “Heidi, Girl of the Alps” and “My Mother’s Travels”, he went on to direct films for Studio Ghibli, which he established with Hayao Miyazaki. Isao Takahata is recognized by animation researchers for his achievements in animation, including his introduction of unconventional character acting and emotional expressions, his painstaking depiction of daily life to give a sense of real life, and his continuous challenge to innovative expressions such as the integration of backgrounds and characters.

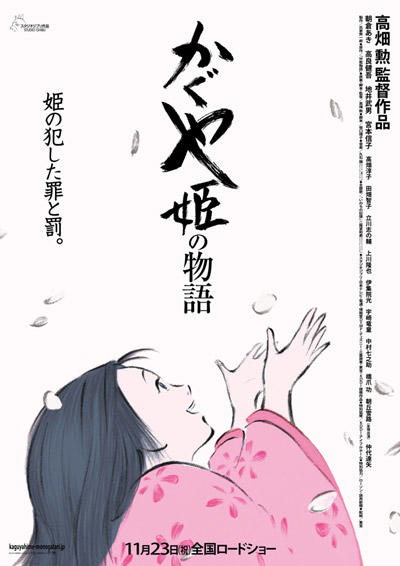

Isao Takahata is known for his “untypical character performances and emotional expressions,” and his innovative methods of expression are too numerous to enumerate. Among such works, as mentioned above, I would like to focus on “film music,” but which works should I pick up? In selecting a specific work, I would like to introduce his posthumous work “The Tale of Princess Kaguyahime,” which I consider to be the work that best sums up the “novelty of expression method.

The Tale of Princess Kaguya

Kaguyahime no Monogatari (The Tale of Princess Kaguya) is a Japanese animated film produced by Studio Ghibli based on Taketori Monogatari (The Tale of the Bamboo-Cutter). Directed by Isao Takahata, the film was released on November 23, 2013.

This is the first film directed by Takahata in 14 years, since “Hohokekyo: My Neighbor Yamada-kun” in 1999. Takahata passed away on April 5, 2018, four and a half years after the release of this film, making this his last work. It took eight years from the start of the project and a production cost of over 5 billion yen, which is unprecedented for a Japanese animation film. In terms of technique, the hand-drawn style that was introduced in “Hohokekyo: My Neighbor Yamada-kun” was also used in this film. In addition, the backgrounds are drawn with a touch similar to that of moving pictures, and the two are combined to create a “single moving picture.

The above is a brief introduction to this work, but what I would like to discuss this time is the music of the last scene of this work. By the way, I have previously introduced “Taketori Monogatari” on this blog.

*For more information, please visit the following URL

The story of Princess Kaguyahime is based on “Taketori Monogatari” (The Tale of the Bamboo-Cutter), which is a tale of a celestial being named Kaguyahime. The story is about a celestial being named Kaguyahime who falls into the human world, interacts with various people, and returns to her home in tears when she is welcomed by the heavens. The climactic scene in particular, in which the separation from the old couple who raised her and the emperor she fell in love with is so poignantly depicted that it is impossible to read the story without tears. In “The Tale of Princess Kaguya,” too, this scene was supposed to be a very moving one. If only that weird song hadn’t played in the background…

This image is from that last scene in which the heavenly beings come to greet Kaguyahime. Normally, a moving or tragic orchestra would have been playing, and the audience’s teary glands would have exploded. However, the music played by Takahata in this scene was a very light-hearted samba-like music. I remember being extremely perplexed when I witnessed this scene in the theater at the time. The tears that had been welling up suddenly stopped flowing, and I had a hard time understanding what was going on. I even felt frustrated that they would not let me cry where I wanted to cry. But I was also sure that I felt strangely disturbed by this uncomfortable direction, and that it was not a simple thing to do. Also, like Hayao Miyazaki’s works, this film is not an exciting adventure tale, so I could not just say, “That was fun! I did not feel happy to see the film. Nevertheless, the cheerful samba and Kaguyahime’s tears kept replaying in my mind after watching the film. However, I was frustrated that I could not verbalize why that movie, and especially that scene, stayed in my mind.

Later, when I came into contact with various discourses on cinematic expression and read Isao Takahata’s past writings, I came to realize what kind of effect the staging had and how it was an inevitable method to support this story. Now then, why did Takahata take this approach? What influenced him? What was the effect of this method? The answer lies in the films of the master filmmaker…

Bolero by Akira Kurosawa

The film is called “Rashomon” (羅生門). It is a 1950 Japanese film by Daiei (now Kadokawa Pictures). It was directed by Akira Kurosawa and starred Toshiro Mifune, Machiko Kyo, and Masayuki Mori. The film is based on Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s short story “Yabu no naka (In the Yabu),” and the title and setting are based on Akutagawa’s short story “Rashomon” as well. Set in the Heian period (794-1185), the film depicts the conflicting testimonies of witnesses and those involved in the murder of a samurai from their respective perspectives, sharply pursuing human egoism, but with a message of human trust appealed in the final act. The film is characterized by the visual expression of Kazuo Miyagawa, who was in charge of cinematography and was conscious of the beauty of silent films. He brought out the beauty of black-and-white images with innovative shooting techniques, such as the beauty of images with strong contrasts of light and shadow, and a technique that was taboo at the time, namely, pointing the camera directly at the sun. The film won the Golden Lion at the 12th Venice International Film Festival and the Honorary Mention at the 24th Academy Awards (now the International Best Feature Film Award), bringing to the world the existence of Japanese cinema, which until then had been largely unknown internationally. It was also a great masterpiece that gave the Japanese film industry a chance to enter the international market.

What did Takahata take away from this classic? What influenced him the most was a scene in the film. In the first half of the film, when the saddle vendor is walking through the forest, the music is in the style of “Bolero”. He discusses this scene in his book, “What I Thought While Making the Movie.

The “somauri” (a small village farmer) moves through the forest. Bamboos rustle and fly backwards at a dizzying pace. The backlight bathes the black leaves and treetops in a mesh pattern. The sun shatters the treetops, radiating a faint, suspicious light. The mohair advances. The edge of a leaf glows. The sharp, thin interplay of pitch-black “shadow” and glittering “light” changes dizzyingly and shoots the eye. A bolero is placed on top of this. The rhythm is unsettling. The effect is immense.

Today, it is not unusual to add Western music to period dramas, but around 1950, it was still a novel experiment. Therefore, most of the audiences at that time were puzzled by the outlandish dramatic music. The melody itself was not dramatic in the sense that it stirred up the emotions of the characters, but rather it was monotonous in rhythm and proceeded in a matter-of-fact manner, as if one were observing the scene from a bird’s eye view. I believe that Takahata learned from the effect of Bolero that music is not merely a tool for heightening emotions, but an expression that has an organic relationship with the images and sometimes brings about dissimilarity. The Oxford Dictionary of Film Studies defines “catabolism” as “in film studies, the term refers to an attempt to create a critical response, as opposed to a passive immersion of the viewer, with the aim of suppressing an intoxicating emotional response to the work. Takahata also said.

Heidi” was still a fantasy in the broadest sense, and with that intention in mind, I drew an ideal image of what I wanted it to be like. However, after that, as a result, I stopped doing fantasy-like works. I began to deal more and more with a world that felt real in everyday life, and the setting was limited to Japan. The reason for this is that fantasy abounds all over Japan (omission). So I have been making my works while always thinking of something that is connected to reality, something that is a little rough and rough. I have been making an effort not to end up saying, “That was good.

In order to achieve the so-called dissimilarity effect, in which the viewer is made to recognize that the world of the work is different from the real world, the animation world itself must be constructed as a believable “real” world with its own reality. It is precisely because the world of the work is a “believable” world that the audience is able to actively view the work. However, this does not mean that there is a disconnection between the two worlds. The original purpose of the dissimilarity effect is to “open up new ways of seeing and thinking about the subject, and to open up new possibilities of perception. To make the audience think and develop a critical eye is Takahata’s true goal. Takahata also uses the catabolic effect of music to wake the audience from their “hypnotic state” and to make them retain their rationality. And the above is by no means speculation on my part. Takahata himself has said something in a past interview that can be taken as proof of the above.

Conversation with composer Joe Hisaishi

Hisaishi: It’s like beginner’s luck. The hard part was after that. Mr. Takahata instructed me not to express the feelings of the characters, not to attach them to situations, and not to stir up the feelings of the audience.

-Everything that might be required of film music was forbidden.

Takahata: Hisaishi-san is exaggerating a bit (laughs). (Laughs.) But he did not want sad music for the sadness of the main character, but music that would accompany the audience as they watch the film and wonder what will happen to them. I thought Hisaishi-san could do it because I heard the music for “The Bad Guy” (directed by Sang-il Lee). I was really impressed. It was music that beautifully watched over the fate of the film.

Hisaishi: Usually, I am asked to express emotional expressions such as joy, anger, sorrow, and pleasure very often. For example, “how I felt when I was moved by seeing the sunset. However, I have tried my best to make films without being influenced by the mood, and “The Bad Guy” was a film in which that worked out well. However, Mr. Takahata’s instructions went beyond that, so it was very difficult. Many of the pictures are abbreviated, like landscape paintings, and he wanted the same for the music. So I thought it would be better to create the core of the work first, so I decided to work on two themes: “The Joy of Life” and “Destiny.

Takahata:

There is a painting called “Amida Raigo-zu” in which Amida comes to welcome you. Since the Heian period (794-1185), many such paintings have survived, and in one of them, a musical instrument is being played. However, the instruments depicted in the paintings are all instruments from the West, which can only be found around Shosoin, and they were rarely played in Japan. So even if you look at the paintings, I don’t think people at that time could hear the sounds. But they also used a lot of percussion instruments, and I was sure that the heavenly beings would come down, sounding joyful, nouveau music with a rhythm that had no worries. My first idea was samba.

Hisaishi:

When I heard about the samba, I was shocked. I thought, “Oh, I wonder how far this film will go” (laughs). But it really turned me on. The entire film is based on Western music and orchestral music, but I wanted to change the music of the Heavenly Host so much that people might think it was a wrong choice of music. But it would not be good to separate them completely, so I thought about it and came up with the idea of adding more and more simple phrases of Celtic harp, African drums, and South American stringed instrument charangos. I took it to him thinking it would be rejected, but Mr. Takahata said, “That’s a good idea.

Takahata:

This may have something to do with Hisaishi-san’s basic idea that film music should be counterpoint to the picture.

Indeed, when I saw the last scene of “The Tale of Kaguyahime,” I was in a state of excitement, expecting an “emotional farewell scene,” but my brain was instantly cooled down by the samba. Then, I was forced to look back at the story from the perspective of a cool-headed critic, wondering “What kind of a being was Princess Kaguyahime in the first place? I had no idea that this was Takahata’s intention at the time, and I could never have understood it. The blurriness I felt at the time was the result of his “iatrogenic” effect, and it was the perfect solution to motivate me to make a permanent effort to understand the story.

Conclusion

I have discussed the work of many artists on this blog. I have discussed the “disturbing hiragana onomatopoeia” of Iwo Kuroda and the “sketchy literary expression” of Yoshimitsu Morita, among others. In retrospect, all of their stagecraft that fosters such a sense of discomfort may be classified as “iatrogenic” effects. What Isao Takahata and his directors have in common is that they do not bury the audience in the emotions of the characters, but let them discover the message of the story in general. That is why their films are often regarded as “difficult” and tend to end up suffering at the box office. However, I believe that in their works, which continue to depict such “dissimilarity” in an honest manner, lies the key to getting one step closer to the truth of this world, and also the opportunity to gain kindness toward our neighbors.

★The writer of this blog: Ricky★

Leave it to us when it comes to cultural matters! Ricky, the Japanese culture evangelist, will turn you into a Japan geek!

Source

Isao Takahata Wikipedia

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya Wikipedia

Film Music and the Death of Fumio Hayasaka

Romantic Album: The Tale of Princess Kaguyahime

Wikipedia