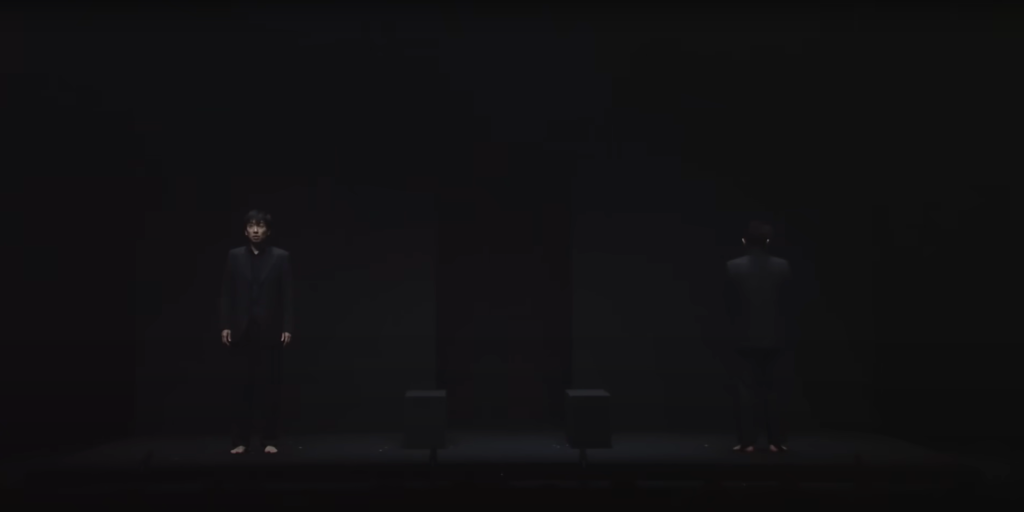

The stage is pitch black. The two boxes placed in the center are also black. The two performers sitting there are also dressed in black. There is no explanation of the setting. There is no clear beginning and end. Depending on the work, there is no dialogue.

Their skit, which could be taken as ridiculous, took the Japanese comedy world by storm for a time.

The comedy group Rahmens, consisting of Kentaro Kobayashi and Hitoshi Katagiri, has not performed a skit since 2009. Since Kentaro Kobayashi announced his retirement from the stage as a performer in 2020, the group has effectively disbanded. Even during those active years, they did their best to keep their TV appearances to a minimum, so nowadays there must be many people who have never heard of them.

Nevertheless, their achievements in the world of Japanese comedy continue to shine brightly. There are countless comedy duos that claim to have been influenced by Rahmens, and even more than 15 years later, YouTube videos of their skits from that time continue to gain views. I myself was also a student of Rahmens’ skits and was captivated by the surrealistic worldview they created.

What was it about their out-of-the-ordinary skits that made them so appealing? I will discuss this question by going back in time to the feelings I had when I was devouring rental DVDs at the time.

Rahmens Brief Introduction

Rahmens is a skit group formed by Kentaro Kobayashi and Hitoshi Katagiri. The group was formed by classmates of Tama Art University while still in school, and performed mainly in theaters with skits described as “artistic,” “intellectual,” “theatrical,” and “absurd.

The two were classmates in the printmaking department at Tama Art University, where Kentaro Kobayashi majored in woodblock printmaking and Hitoshi Katagiri in lithography. The name of the group was given for the time being in order to compete in the intercollegiate competition, and was decided upon when Kobayashi called from a ramen shop one day and suggested, “How about Ra-men’s?” Kobayashi writes the scripts for all of the films.

Rahmens’ SKIT

In all aspects, Rahmens’ SKIT was unparalleled.

Current events are basically not incorporated because they shorten the life of the piece. Even gags that have become standardized are not employed because the difference in prior knowledge between first-time viewers and regular audience members can change the way they feel about them. They seem to have started with simple stage design and costumes in pursuit of laughter that can be created only with the body. By the third performance, the stage is covered with plain cloth for the background, and the props consist of only minimal elements, such as boxes. This shows Kobayashi’s belief that if the stage and costumes have prominent parts, even if the script is weak, the show will be successful. Also, by making the plain costumes more anonymous, Kobayashi aims to evoke a reality of life that is familiar to each of the audience members.

Before I introduce the actual work, let me give you a few points in advance.

(1) Betrayal of maximum depth

(2) Audience participation

(3) The material of fear

This, I believe, is the essence of Rahmens’ skits and the basis for their unparalleled works (although there are many second-run performers who imitate their works, but the quality is overwhelmingly inferior). ) Their works sometimes seem to take a sudden and unbelievable turn, but if we analyze them with this point in mind, it will help us understand a little better what they are trying to express. Let us introduce some of their actual works and try to unravel them in detail.

Typical skit

・Nipon(It is important to be Nipon, not Nippon) in Wonderland

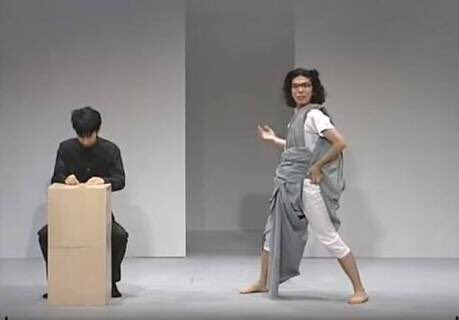

The skit is about a foreign teacher, Kobayashi (standing), giving a lesson to another foreigner, Katagiri (sitting), about the country of Japan. Their language is one that I have never heard before, and they are probably from a fictitious country. The setting seems to be a Japanese language school, and Kobayashi teaches Katagiri in heavily accented Japanese, sometimes in the language of that fictional country.

As you can see in the image above, the extreme abstraction of the space is confusing at first, but it gradually becomes less and less strange, and before you know it, it looks just like a classroom. It is a reminder of the power of human imagination as well as the acting ability of the actors.

As for the content, Kobayashi listed the prefectures of Japan, starting from the north, and explained the characteristics and specialties of each prefecture.

Katagiri repeats the explanation of the characteristics and specialties of each prefecture.

The first funny point is that, despite being a teacher, Kobayashi’s knowledge is full of prejudices (sometimes completely wrong), but Katagiri, as a student, cannot correct them and recites them without question. For example, the following is an example.

Kobayashi: Hokkaido

Katagiri: Hokkaido

Kobayashi: Half of the residents are bears

Katagiri : Half of the inhabitants are bears

Kobayashi : The other half are crabs

Katagiri: The other half are crabs

There are multiple twists here. For example, Kobayashi’s second line is not “the inhabitants are bears,” but “half of the inhabitants are bears,” which is wonderful. This makes the audience think inwardly, “Of course not,” but at the same time, they subconsciously assume that if half of the residents are bears, then the other half must be human. But then Kobayashi says, “The other half are crabs. The audience’s expectation is greatly betrayed by this so far-fetched development, and laughter ensues.

This scene would fall under (1) [betrayal of the greatest depth] mentioned above.

Comedy, in the first place, stems from the destruction of common sense. The deeper the destruction, the more profound the laughter. In this case, let’s look at…

Common sense: “Residents are people.

The first layer: “The residents are bears.

The second layer: “Half of the residents are bears.

And in the case of the Rahmens, it goes even deeper,

The third layer “Half of the residents are bears, and the other half are crabs.

The third layer is even deeper. When the story goes this deep, the audience can no longer make predictions. The pleasure of betrayal is then amplified, and it comes back as a big laugh.

Rahmens also easily breaks down even the stereotype of “roles” in a comedy group. In most Japanese skits, there are two roles: the Boke (the character who says funny things in the skit) and the Tsukkomi (the person who corrects the Boke’s funny things). Tsukkomi is the equivalent of a straight man.

In comedy entertainment, both old and new, the presence of a straight man keeps the story moving at a brisk pace and helps the audience to understand the story, which in turn helps to generate laughter. For example, in the above exchange,

For example, in the above exchange, when Boke says that half of the residents are bears and the other half are crabs, Tsukkomi(=straight man)would normally say, “That can’t be true.

However, Rahmens intentionally excludes this role. This leads to (2) [audience participation]. Boke’s words floating in the air were intended to be a “Tsukkomi” (a kind of “Where did all the Hokkaido people go? “) In other words, the audience is made to become the “Straight Man” themselves, participating in the skit and enjoying it together with the performers as if they were the inhabitants of the world.

However, this structure also entails a certain risk. The elimination of Tsukkomi’s role not only prevents the production from building tempo, but also puts the audience at a critical risk of missing out on some of the funny parts of the show. Without such aids, some people may not even understand what is going on in the first place in a work such as Rahmens’, which is based on laughter that is not dynamic in nature. Nevertheless, Rahmens accepts this concern and still maintains its audience-participation charm because it believes in the expansiveness that can be created by leaving a margin of imagination rather than forcing an interpretation through Tsukkomi.

The skit continues with a series of funny introductions of the prefectures of Japan, ending with Okinawa. The ridiculousness never loses its momentum, and the film runs like a runaway locomotive. However, this film is not just an unconventional work. By setting the characters as “people from a fictitious country,” the film avoids unnecessary claims.

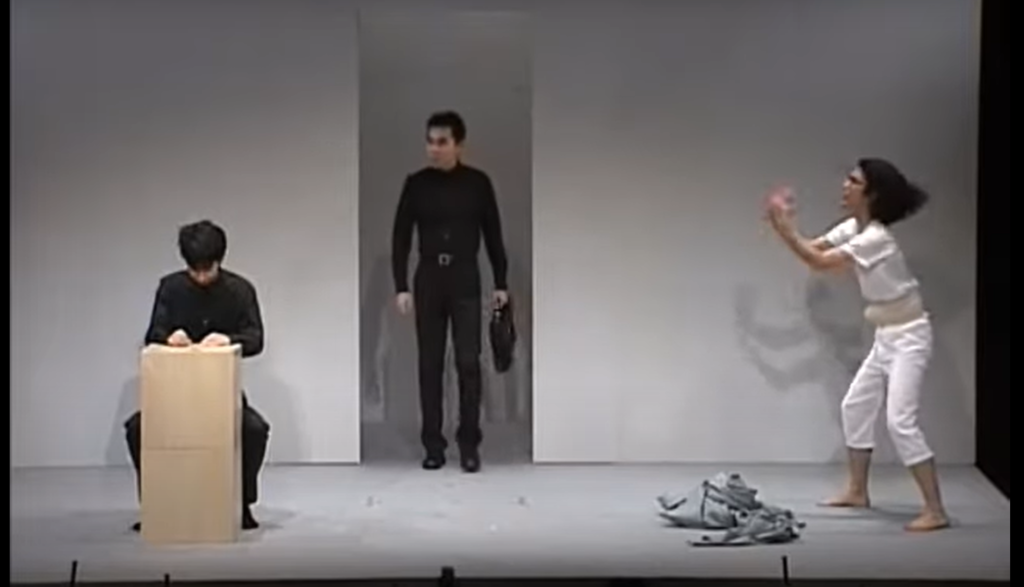

・Takashi and his father

In this skit, Takashi, a student preparing for an entrance exam (Kobayashi, sitting, plays Takashi), and his father (Katagiri) play out a skit in Takashi’s room. Kobayashi, who plays Takashi, does not say a single word. Not only does he not speak, but he does not even pay attention to his father’s antics right beside him. He is determined to ignore the father’s antics. Undeterred by Takashi’s cool-headedness, the father continues to act nonsense, saying, “Look, Takashi” (the content is too outlandish to be verbalized).

Kobayashi, who plays Takashi, bursts out laughing in the middle of the film (of course, this is a kind of invitation to laugh, but the audience can’t help but laugh along with him because of his calm and composed manner until the middle of the film), Katagiri, who plays the father, sits down in the middle of the film because he is tired from too many crazy actions, giving it a jazz-like realism that made it difficult to tell where the script and ad-libs came from.

The skit, however, ends with an unexpected turn of events. Toward the end, a mysterious man suddenly appears on stage.

Mystery Man: Good for you, Souichirou, studying?

Kobayashi: Welcome back, father!

Yes, this mystery man was the real father. The boy played by Kobayashi was also not really named Takashi, but Souichirou. Katagiri says this as he watches the two of them get along.

Katagiri: Takashi, instead of playing with your real father, let’s play with this fake father.

In other words, Souichirou was not ignoring Katagiri; he was not really seeing him. Katagiri, however, did not mind this sudden turn of events and started fooling around again, as if nothing had happened. After a while, Katagiri leaves them on stage and leaves. The skit ends, leaving the audience feeling like they have been pinched by a fox.

The ending is a bit chilling. In this way, the skit by Rahmens does not just end with a laugh, but often, without warning, it is a performance that can only be described as a horror. This is (3) [the material of fear]. What had been going on in a good atmosphere, filled with warm laughter, was suddenly cooled down. The audience’s laughter suddenly stops, and the last act comes to an end without the audience’s brain being able to comprehend what has just happened. This kind of phenomenon is not seen on comedy shows these days. In contemporary Japan, laughter is exclusively aruaru (common occurrence), and there is a tendency for everyone to think that works that make everyone laugh with ease are good. This is because laughter is always sought after and consumed as a “tool to heal people’s hearts. However, from Kobayashi’s point of view, laughter is only one of the tools he uses to express his inner nonsense. Laughter, metaphor, the ridiculous, abstract space, and fear. Laughter or not, it doesn’t matter what it is, as long as it shatters stereotypes.

The presence of a freezing engine of fear cools the heat in the brain, allowing the audience time to look back at the skit world with a cool head and analyze the tricks Kobayashi has set up. What was this fake father played by Katagiri? Why was he calling himself different names… The reason for the audience participation and the material of fear is that we trust in the literacy of the audience. We have chosen this unusual format because we trust that the audience will take the skit as it unfolds and analyze it for themselves.

Conclusion

As mentioned above, in contemporary Japan, comedy on television is dominated by “just-right” and “homey, heartwarming” “aruaru,” either because of the tonal pressure of the times or because of the wishes of sponsors. As if in reaction to this, a kind of race to see how extreme one can be in one’s words and actions is taking place on the Internet, where public ethics are not so strict. Eroticism, invective, vulgarity, and the like abound. In any case, there is no doubt that the laughs on TV and on the Internet are similar and the same. How on earth did we end up with such a disastrous situation?

Perhaps their early retirement was a reflection of the current trends of the times. The Rahmens were a legendary comedy group that once broke new ground in the world of Japanese comedy. Who in modern Japan has truly inherited their DNA? It might be fun to take another look at the world of comedy on TV and the Internet from this perspective.

★The writer of this blog: Ricky★

Leave it to us when it comes to cultural matters! Ricky, a Japanese culture evangelist, will turn you into a Japan geek!

Source

Rahmens Wikipedia