Who is the most famous novelist in Japan? For living writers, it would be Haruki Murakami, Keigo Higashino, and Kanae Minato. If they are dead, then Dazai Osamu, Akutagawa Ryunosuke, and Mishima Yukio, to name a few. These are the people whose names appear in Japanese language textbooks, and there is no doubt that they will continue to be well known for a long time to come. But even so, it is not easy to say yes when asked if they will ever be used as portraits on Japanese banknotes.

Recently, the Bank of Japan announced that Shibusawa Eiichi has been selected for the 10,000 yen bill in 2019 (to be issued in 2024). In the past, Yukichi Fukuzawa, Taisuke Itagaki, and Hirobumi Ito have also been selected. In other words, the criteria for the portraits on Japanese banknotes are likely to be people who have made political and economic contributions to society, such as the above-mentioned members.

In this light, the fact that Soseki Natsume, a mere novelist, was selected for the 1,000-yen bill for more than 20 years from 1984 to 2007 is an unusual selection. (Higuchi Ichiyo, another novelist, was selected for the 5,000-yen bill, but her case is excluded here because her selection was in line with the progress of women’s social advancement at the time.)

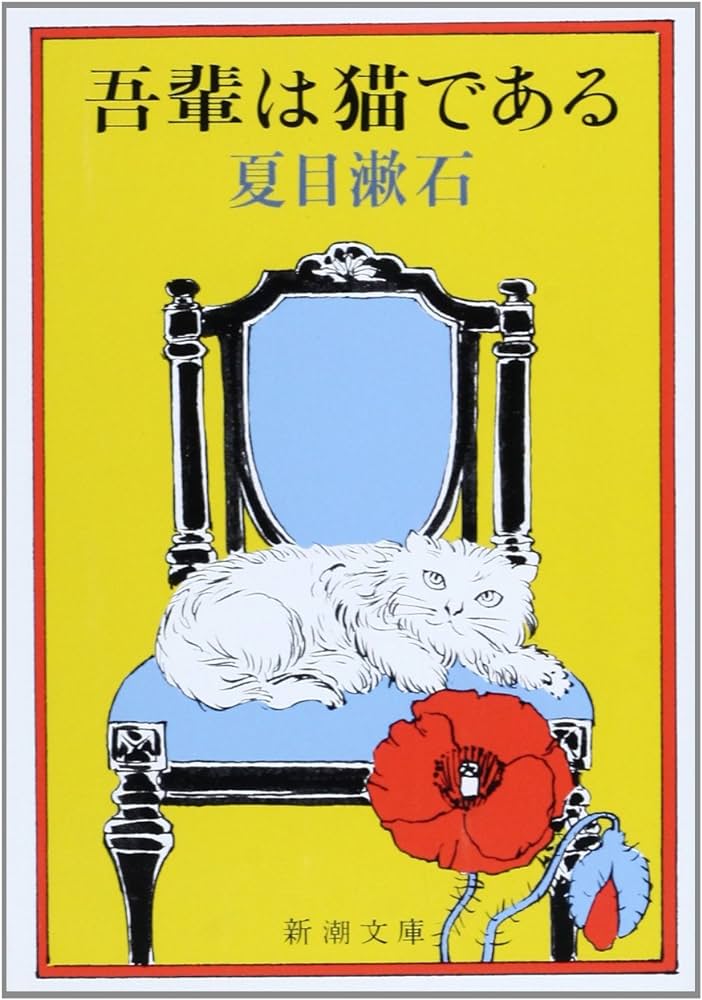

What I am trying to say is that the reason why Soseki has been selected as the most frequently used 1,000 yen bill for a long time is due solely to his literary value and name recognition. I am a Cat,” “Bo-chan,” “Kokoro,” “Sanshiro,” and so on.

He produced masterpieces that are well known to all Japanese, and his critiques and research papers are still being published more than 100 years after his death, not to mention in Japanese language textbooks. (His recognition overseas is not as high as it should be. (Mishima, for example, is much better known, as he was a hot topic in many fields other than literature.)

What is the true nature of the centripetal force of his literature? I believe that it may lie in the movement for unification of the written and spoken word. In this blog, I would like to mainly explore the true nature of this movement.

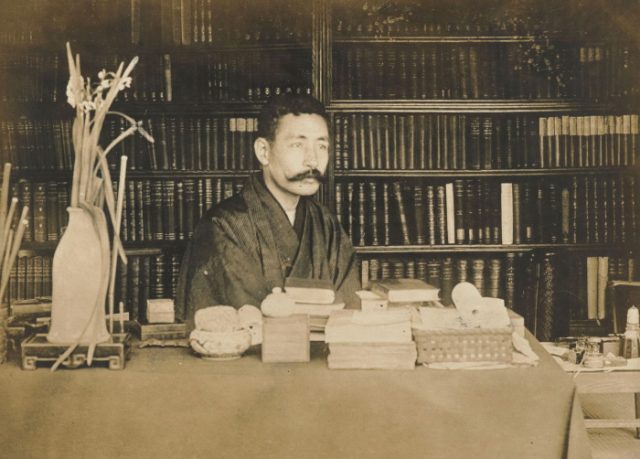

About Soseki Natsume

February 9, 1867 (January 5, Keio 3) – December 9, 1916 (Taisho 5)

Japanese teacher, novelist, critic, English literature scholar, and haiku poet.

After graduating from the Department of English Literature at Imperial University (later Tokyo Imperial University, now the University of Tokyo), he worked as a teacher at Ehime Prefectural Junior High School in Matsuyama and as a professor at the Fifth Higher School in Kumamoto, before going to England to study. He lived in Camden and Lambeth in Greater London.

After returning to Japan, he taught English literature as a lecturer at Tokyo Imperial University, and after resigning that position, he began writing novels. Despite suffering from neurosis, he produced masterpieces, and died of a stomach ulcer at the age of 50 in 1916, while working as a novelist for the Asahi Shimbun newspaper. During his life, he devoted only 10 years to writing novels.

Soseki Natsume and Identity

Soseki Natsume was born and immediately put up for adoption. He spent his years until the age of nine with a couple, Shonosuke Shiobara and his wife, who were his father’s students. For a long time, he thought they were his real parents (and the Shiobaras lied about it). However, when they were sent back to their parents’ home because of Masanosuke’s infidelity, they were told by the maid that they were their real parents, and they finally understood what was going on. This must have been very painful for Soseki as a child. Soseki was the eighth child, and even though he returned to his birthplace, his father, Naokatsu, did not love him at all. Soseki was forced to live in a series of homes, and he could find no place to stay.

Am I needed? Am I replaceable?

He must have felt like he was being toyed with by capricious adults. His childhood was filled with wariness of the “arbitrary” attitude of these people.

How on earth did he acquire an identity in such a situation? Rather, how or from where do we usually acquire our identity? The easiest place to think of is the family. When one is loved and nurtured by one’s own parents, one’s identity as a “family member” may first be nurtured.

In Soseki’s case, however, he stumbled at the starting point. Blood ties, family environment, and other things that would normally be considered solid foundations were, in his view, “arbitrary” and “replaceable. Rather, he thought that true identity might be found in such “nihilistic” conditions.

Therefore, he tried to find his identity in “creation. For him, creation transcended mere occupation, hobby, and the like.

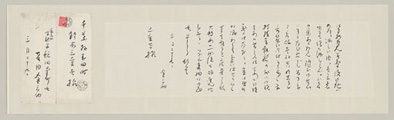

I would like to do literature with the same fiery spirit of the Meiji Restorationists, who were in a life-and-death struggle for their lives. -Letter for Miekichi Suzuki dated October 26, 1906

【Genbun-ichii】agreement between words and sentences

While we are on a different subject, here is a brief explanation of the theme of this issue [Genbun-ichii].

Gembun unification refers to writing sentences using a colloquial style that is close to the spoken language used in daily life, or, as a result, sentences written in a colloquial style.

In Japan, where Japanese is the main language, this practice came to replace the previously used literary style in the Meiji era (1868-1912), as a result of the growing movement for unanimity between words and sentences. By the end of the Taisho era (1912-1926), the unification movement was considered to be complete.

The “unification of speech and writing” aimed to write reality more realistically, transparently, and directly. In other words, the written word ceased to be a rhetorical tool and became a tool of translation and communication to reflect reality. The directly seen landscape was also to be described as it appeared to the eye. In other words, with the introduction and absorption of Western philosophy, nature was objectified through science and art, and the modern concept of landscape and subjectivity was discovered. These discoveries led to the growing popularity of naturalism in its various forms. Writers departed from the elegant and far-fetched style based on traditional imaginative concepts, adopting a personal point of view and striving to capture the movement of nature without beautification or exaggeration, at least in theory.

The above is the textbook view, but in other words, the unification of the written and spoken word was merely a part of the movement toward Westernization during the Meiji Restoration.

Until then, there was no such concept as a “standard language” in Japan. However, the Meiji government, which was intent on Westernization, launched the “Tokyo Standardization Project” as a foothold for centralization of power, and had it semi-forcibly propagated throughout the country.

At that time, there was a disconnect between the written and spoken languages. Until then, writing had been a formalistic, rhetorical tool, and at the same time, it was centered on Chinese characters. For example, the kanji character “大河” can be read either as “taiga” or “ookawa”. The two have different meanings, which means that the interpretation of the characters depends on the reader. Even this one part of the text shows the interchangeable structure and diversity of written expression.

However, with the movement for unification of the written and spoken word, writing was being transformed into an “expression of feelings. In other words, the concept of “writing = emotion” was born. The focus has shifted to hiragana instead of kanji, and writing has been transformed into something irreplaceable. Today, for example, most sentences are written in colloquial language, as typified by smartphone messaging applications. For example, “[Maji de yabai(Seriously dangerous)]is a sentence that relies on hiragana and is directly linked to emotions.

Soseki’s Battle, Peculiarities of “I am a Cat

- Soseki’s Battle

Soseki was born and came into contact with literature at a turning point in this movement toward unification of the written and spoken word. Naturalistic literature, in which “what you see is what you get,” was gaining in popularity, and history was being falsified to make it seem as if this was the true expression of writing.

However, Soseki, who had studied English literature in England as a correspondent of the Ministry of Education, and by extension, the origins of world literature, was wary of the “arbitrariness” of such language. He believed that literature should be “replaceable. Literature is not a means of expression directly linked to a situation or emotion, but rather a more multifaceted form of expression.

Let us examine “I am a Cat,” which seems to reflect Soseki’s thought most strongly.

- I am a Cat” Discussion

This work is characterized by the fact that it is narrated in the first person pronoun by a cat who calls himself “I.” In other words, the animal cat is the viewpoint and animal (person), and at the same time, the work is composed as the narrator. The narrator’s first-person pronoun “I” itself is part of the work’s character. This first person pronoun is unique even among Gekishi’s works. The “cat,” which is the animal that provides the point of view, observes the state of the human world, in contrast to the generally human-dominant position of the cat. In other words, the subject of the image is “my cat,” and the object of the image is the human being itself. In particular, the comical patterning of the daily life of the cat’s owner by “I” am the Cat is a narrative that, while based on the naturalistic literary principle of “copying what you see,” reverses the superiority of humans from the standpoint of an outsider, looking down from above. The “I” in “I am a Cat” is a first-person narrative built on such a complex background.

At the same time, this work has nuances unique to the Japanese language. This is both a complication and a superiority of the Japanese language. In Chinese, which uses the same Chinese characters, there is a way of saying “I am,” but it does not have the nuance of arrogance that Japanese has. The Chinese “Jigen” and “Jikkai,

When I tried to look up the meaning of “吾輩” in “現代漢語調典”, “辞源” and “辞海” do not contain “吾輩”. In the “Gendai Kango Shuseki,” it only means “to use as a first-person pronoun. The Chinese translation of “I am a cat” is “我是猫,” which uses the neuter first-person pronoun “我. Therefore, Chinese studies of “I am the Cat” have largely overlooked the characteristics of the first-person pronoun tone of “I” even when studying the uniqueness of the cat’s point of view.

In other words, even a single kanji character has a number of meanings. They are not merely mediated as an outpouring of emotion, but exist as a kind of concept that is always interchangeable.

Conclusion

Soseki was a child who could be replaced.

Let me conclude with an excerpt from “In the Glass Door,” which is said to be Soseki’s autobiographical novel, and which is famous for its famous sentence.

When I told my story, I was able to breathe in relatively free air. Even so, I had not yet reached the point where I could remove all color from my life. Even if I did not have the pedantry to lie and deceive the world, I still failed to disclose the more vile, the more evil, the more disgraceful my faults. Someone once said that no matter how much one traces the confessions of St. Augustine, Rousseau, and Opium Eater, the true facts cannot be described by human power.

And what I have written is not a confession. My sins, if they could be called sins at all, would have been portrayed only from a very bright place. Some people may feel a certain discomfort with that. But I myself am now straddling that discomfort and smiling as I look out over humanity at large. I look over at myself, the person who has written such trivial things, with the same eyes and feel as if I were a stranger, and still I am smiling.

This is where the sadness, humor, and comedy of Soseki’s literature all come together.

Soseki asserts that it is impossible to describe the true nature of a person. He knew that no matter how much he tried, he would be swallowed up in a sea of arbitrariness, and nothing would await him but emptiness.

But he could not stop creating. It was only there that he found a hint of identity. It was a very uncomfortable process. He went to great lengths to prove, without being asked, that he was replaceable. At the same time, it was also a rebellion against the conventions of the times, and must have been met with a strong public outcry.

However, he describes his state of mind at that time as “smiling while looking out over a wide area. I can’t help but think that this is Soseki’s way of being strong. By actively ridiculing his own life as a ridiculous one, he is rather protecting it. I love Soseki’s literature anyway. Although it is difficult to see his face on a bill anymore, his many famous writings will remain in people’s hearts forever. Especially for those who have lost sight of their own identity, his compassionate words will speak to them.

Sources

Soseki Natsume Wikipedia

Soseki’s Essays on Soseki (Gyojin Karatani)

The Transition of the First Person in Japanese Literature during the Meiji Period (Qin Lele)

Soseki Natsume: Inside the Glass Door (Soseki Natsume)